Preface!

My wife and I decided to see the movie The Beekeeper in theaters back… well, back when it was still in theaters, and since then, we’ve watched it about a hundred times at home.

The funny thing is, I’m not even sure we really enjoy the movie for its quality. In fact, I’m sure we don’t. We enjoy it because it’s… what’s the word… flippant? It’s just Jason Statham fighting the world, one scammy call center at a time.

But I think what really makes this movie so infinitely rewatchable (yes, infinitely, just come over some night, there’s a 50% chance we’re watching it) is that in the midst of this action is a kernel of truth—call centers are the worst, and the whole world is corrupt.

So… two kernels of truth. But those little truths are so accurate that no matter how little the movie depends on it, it makes the action that much better.

Which has a lot to do with Tank Chair, believe it or not.

Preface over

For the longest time, I had a vendetta against Michael Bay films because they were all explosions and very little heart. So much fighting, not enough to fight for. Well, there’s always the destruction of the world to fight for, but that’s so macro, not to mention overdone, that it becomes meaningless.

Let’s all watch supersized robots fight for the fate of humanity. Yeehaw.

Don’t get me wrong, it has its place, but if you’re looking for heart, for meaningful character growth, you won’t find it there. At least I didn’t.

But there are plenty of high-action stories with heart. My question is always which came first, the action or the heart. Did they want to have big robots duking it out and then nestled a little genuine human connection in there just for shits and giggles, or was the primary goal to create a meaningful story and oh, by the way, it takes place in an intergalactic conflict?

You may be asking what the difference is. And to be fair, maybe the difference doesn’t matter in the end, so long as the heart is well told, and the action is explosive (ha). I’d be willing to concede that point. If you told me that Tank Chair began as the title suggests, with a badass chair and a deadly assassin sitting in it, and then later on they came up with the creamy center of a sibling relationship, I’d probably just… grunt or something. Because however they got there, it worked.

And that’s the thing with Tank Chair. Whatever excessive violence or completely unhinged killers make their way onto the page and are subsequently killed, it all points back to the core of the story—two siblings who want to have each other’s company again.

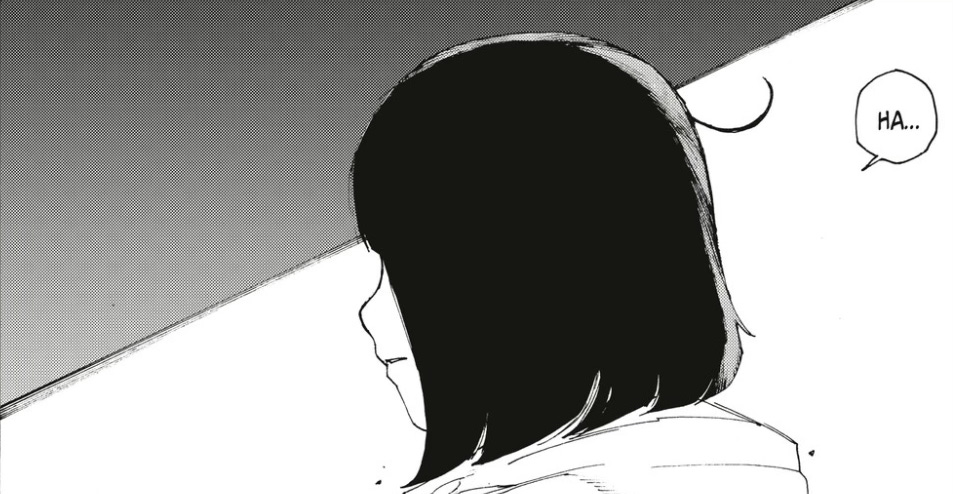

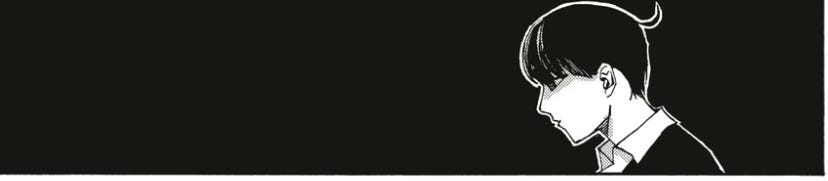

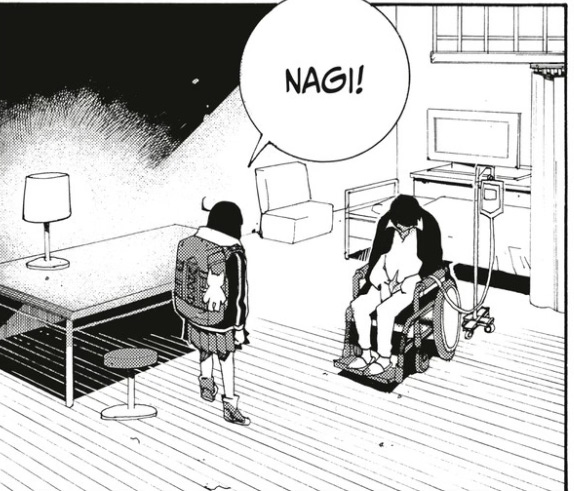

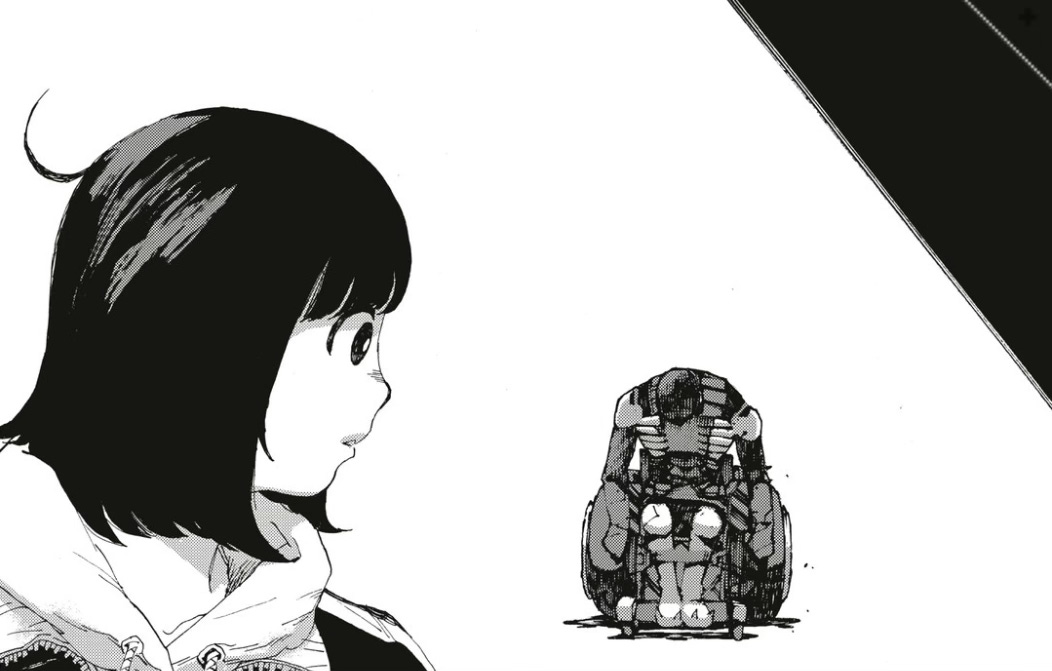

A brief summary of Tank Chair: The deadliest assassin ever—Nagi—is in a coma, confined to a wheelchair. But his sister—Shizuka—discovers that, when faced with deadly intent, Nagi wakes up from his coma temporarily to dispose of the threat, and then he lingers for a bit to reconnect with his sister in touching conversations where they cling to their sibling relationship. So Shizuka keeps hiring new assassins to try to kill her brother so he will wake up, albeit briefly. Oh, and Nagi’s wheelchair is a vessel of death and destruction.

Now you know all you need to know.

This is a series that has tons of action, but it’s never about the action. At least not exclusively. So many Shonen series in particular are built for action. They use the in-between to reset expectations, have a little cool-down, chat a little, but then they throw readers back into high-octane battle royales. Rinse and repeat, it works, right?

Tank Chair never feels like that. Tank Chair makes the in-between portions the whole point of the story. Add in the organic tension of the ticking clock—Nagi is always going to go back into his coma—and this is a brilliant case study on how to have so many story elements all working towards a singular, simple objective. Even when, on the surface, it may look like a death match on paper.

So many series out there promise big fights, big muscles, big magic, big everything. Explosions. Fisticuffs. Yeehaw. Few series are able to balance the high octane with the other story elements. The fights take over, it’s what readers wait for.

Interestingly, my beef with Jujutsu Kaisen was essentially this concept in a nutshell. The most I enjoyed JJK in the recent downfall was in the brief, calm chapter when Yuji and Sukuna are spending time together. After chapters of endless fighting, that felt like such a bold storytelling step, and it worked well. It just ended too soon.

I reference The Beekeeper in the preface, and I want to expand on that here. If The Beekeeper was a manga, and had space and time to play with theme and character, it would legit be amazing. Incredible. Monumental. That kernel of truth at the heart of the action is always on my mind. Every time I see certain world events, I say to my wife, or she says to me, “I wish we had a beekeeper to make this right.”

Tank Chair’s unhinged and frantic battle sequences are a delight on their own, but when you stop and think about why this action is happening, it makes the action that much more important.

Do you have that same response to Transformers, or to any other flat action movie where the world is at stake, but little more? Sorry, I thought I was over my vendetta against Michael Bay but I guess I’m not.

The point is, if you’re telling a story that’s high action, intense battles, and life-or-death character interactions, the downtime between such fights needs to amount to something more. It’s the same thing I always say about horror. The horror that really sticks is the horror where you care about the characters being attacked, or haunted, or possessed.

Otherwise, it’s just surface value. Which has entertainment value, but does it have sticking power? No.

In Tank Chair, everything serves the purpose of Shizuka and Nagi being siblings. This is action that follows plot, not vice versa. It’s action that serves the end goal of helping these two siblings reconnect. Honestly, it’s so crafty that it almost feels like a cheat code.

Another manga example—Wind Breaker. And I can’t mention it without adding—I adore Wind Breaker. So much. It’s like that friend that’s always there for you, no matter how far you drift away.

I digress.

Wind Breaker has a lot of fights. And their action sequences are bananas in the best way possible. But all that action drives the reader to the meaningful moments Sakura has where he’s learning to build his trust. The best example is from the Roppo-Ichiza Arc, where Furin has to face Endo and his band of rogues.

Sakura has to fight alongside Sugushita, who is in many ways Sakura’s rival, even though they fight for the same team. Like Bakugo to Midoriya (I mean Roy, sorry honey… that’s an old joke). By fighting alongside Sugushita, Sakura has to grow. He has to reevaluate himself. Amidst all this action, as a reader, I couldn’t wait until the action was over to see how Sakura and Sugushita move forward.

It’s action with a purpose.

This has become the central theme of MangaCraft—every story element gets better when it’s working alongside other story elements. Action by itself? Fun. Action that advances character? Dynamite. And also fun.

Tank Chair’s version of action with a purpose is a cut above because it’s overt, but not cheesy. It’s obvious, but not distractingly so. I haven’t gotten deep into the series, at least not deep enough to see how things will unravel the deadlier these assassins get, but seeing how the series is prioritizing the emotional growth of its characters alongside the action gives me complete confidence that wherever it goes, it will serve that central sibling relationship in the best way possible.

Hey, creatives. Action for the sake of action is fun, but any action scene levels up when it’s in the name of the deeper theme of the story—the major dramatic question, if you will. So let’s take an action scene, could be a fight, a chase, a game of dominoes, whatever.

First, ask yourself how this serves that central theme. Both the activity itself (for instance, why would a fist fight be particularly important to your theme as opposed to a verbal argument), but also in how it’s portrayed. Second, let’s slip some more meaning into the action. That doesn’t mean you slow the action down, it just means you be a bit more intentional with what the action is pushing readers towards.

Hey, fans of Tank Chair. Okay, I just gushed about how action should have meaning along with it, but I have to ask—favorite assassin so far?