Preface!

Back when I first wrote about Dragon Ball, I mentioned how I was intimidated to be writing about one of the most prominent stories in the history of the world. Well, I’m feeling that again with Akira.

I have never in my life heard a single mutter of discontent about Akira, either the movie, the comics, the anything. And having seen the movie at long last when Kodansha House popped up like a little slice of heaven in NYC last fall, I was ready to go wholly into this universe.

Needless to say, I’m quite pleased with what I read.

Preface over.

There’s an inherent value to a story that follows a very simple “good vs bad” set-up. There is a good faction fighting a bad faction, it leaves readers very set on what they’re rooting for, and it also opens up the possibility of fun little complexities when something doesn’t fit perfectly into this mold.

But then you have stories like Game of Thrones. The whole shtick of Game of Thrones is that there are no good or bad factions, just morally gray factions that don’t agree with other morally gray factions and inevitably kill each other over it.

While there is zero stability to be found in such set-ups, because readers can’t shoehorn themselves into favorites by morality, that uncertainty surrounding the competing factions is its own brand of compelling and, arguably, much more compelling, at least in concept.

Then there’s Akira. If there were ever to be an imminent need for me to describe Akira in one word, it would, hands down, be ‘compelling.’

Before we get into Akira, here’s what you need to know.

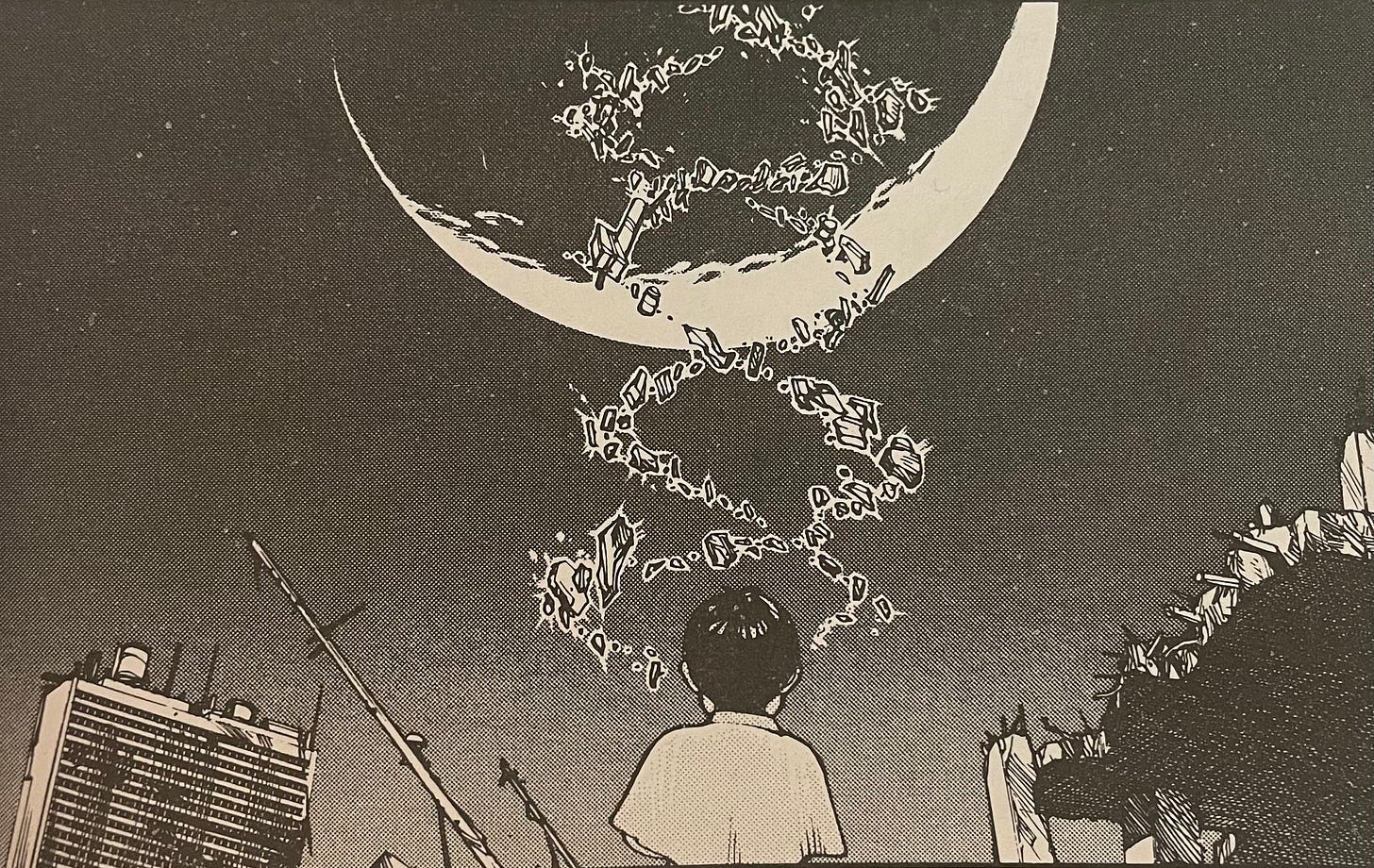

It’s the future. Tokyo is engaged in some serious scientific activity, including harnessing special powers in certain young people who have been experimented on to the point of having superpowers. This leads to issues when those young people go rogue and literally destroy large swaths of the city, then proceed to establish their own little empires.

Chief among these players is the eponymous Akira, the most powerful young child, who can literally become something like a nuclear bomb on his own. Then there’s Tetsuo, once a hero, now something of a delinquent with powers he doesn’t understand. Akira is worshipped as a messiah of sorts in his own little empire, but elsewhere, other super-powered products of this secret program are running their own little kingdoms. Suffice to say, they don’t all get along.

And that’s all you need to know.

Akira is a complex story. There are lots of factions and factions within factions, lots of characters, lots of conflicting view points. Many characters you may think of as protagonists die and disappear for whole volumes or change their role in the story entirely over time.

All that said, Akira is masterful at maintaining such an air of uncertainty that nothing ever feels safe. Meaning that, by extension, the characters in the story don’t feel safe, which means readers can never rest within the pages of the series. If story is all about tension—and many would say that’s the dominant factor in retaining readers—then Akira is a masterclass. And despite all of its complexities, nailing down where that tension emanates from is simple enough.

It’s all from power dynamics.

There are multiple factions that come and go, powerful characters who ebb and flow, allegiances that bend or break, and all told, it’s really hard to ever understand what exactly the big picture threats are and how long they will last. That may sound confusing, but I mean this in the best way possible.

For instance, after Akira goes all boom-boom, destroys a large chunk of Tokyo, and reshapes the fabric of Japan, there are so many factions competing for power.

The Tokyo Empire run by Akira and the volatile Tetsuo. They are militant, aggressive, and the primary issue.

Miyako’s Monks, run by the super-powered Miyako, who are primarily peaceful and look out for everyone they can.

The Kaneda and Joker biker gang within Miyako’s Monks.

The Americans, full of military might and ignorance.

The scientists within the American war machine that may or may not align morally with their employers.

A rebel faction that is hard to pin down.

This reflects the previous arc of the series, where you have the Akira Project faction, the government military, and a similar rebel faction that’s hard to pin down. Then you have characters like Nezu who flitter between these factions seamlessly, despite being his own faction himself, complete with loyal retainers.

After Akira does his thing, all the factions of the initial arc are broken and that void is filled by new factions, but the power dynamics have all shifted. The power players from the Akira Project have become the rebels. The Colonel, who was framed as the most powerful entity in the first arc of Akira, is now a solo vagrant wandering the wasteland. And in the second iteration, Tetsuo’s flittering between factions is the new Nezu, who has also been reduced to a shadow of his former self.

It all begs the question, who exactly is in charge here? Is any one person powerful enough to guarantee the safety of their followers? The short answer is ‘no.’ And that’s all for the best when it comes to narrative tension.

I want to go back to Game of Thrones for a second, because that’s the best comparison here. Game of Thrones has numerous power dynamics, houses and kingdoms that vie for supreme authority, and while no one ever wins, plenty of people lose.

And by lose I mean die.

House Stark has some decent holdings in the North, but then Ned goes and loses his head and suddenly they’re going to pieces, but House Lannister has their own problems, not least of all incest, and don’t count out Pedro Pascal and his fellas in the South. Every few battles or political movements or beheadings, a new shift shakes up the dynamic.

It’s constant uncertainty.

Akira masters this too.

Snapping back to the good vs evil framing for stories, let’s look at the original Star Wars trilogy for reference. It’s only rebels vs Empire. When the Rebels score a victory, momentum moves, but that momentum is linear. It’s either going in favor of the Rebels or against them.

Stories like Akira or Game of Thrones have minimal linear momentum. When House Stark goes to bits, it’s not all directly in House Lannister’s favor. It gets stretched and pulled all across Westeros.

Same with Akira. When Akira’s followers fight Miyako’s monks, the battle may have linear momentum, but the big picture effect of this battle isn’t a straightforward push and pull, it stretches to all different corners of Tokyo.

And what’s even better is people like Nezu, or the Colonel, who lose all their standing after the first arc, are still lingering in the second arc. They still have a part to play, and as opportunities to seize power open up from Akira and Miyako weakening each other, the power dynamics present even more opportunities to shift.

But that opens up another exciting realm of potential within these uncertain set-ups—when characters do flip allegiances or factions. Again, this does work in good vs evil stories, but it is—you guessed it—linear. When Saruman goes bad in Lord of the Rings, it’s pretty straightforward. What once was good now is bad. Dynamics change, it ripples across Middle Earth.

Or, if we want to go super retro, when Bowser joins Mario’s party in Super Mario RPG? That was exciting. It introduced so many fun dynamics I never expected to see in the mushroom kingdom. But it’s a linear swap, evil becomes good.

Then there’s Game of Thrones, when characters like Jaime Lannister and Brianne team up despite initially hating each other, or Arya Stark and The Hound. These are characters who, because of their differences and having to find a way to work together, open up so much more complexities than “good goes bad.”

Akira does this with the Joker and Kaneda and with Colonel and Kei. Well, the Colonel and practically everyone. He was the villain—in the simplest of terms—in the first arc of Akira, and he becomes a companion. No longer a head honcho of a secret and powerful organization, now he’s just a regular dude. That’s a fun dynamic. It always will be. But just like with Jaime and Brianne and Arya and The Hound, it’s filled with uncertainty. A shifting power dynamic that has so many possibilities.

It’s like trying to walk during an earthquake—unstable. Only you’re doing it in a book, which is way more safe and fun.

It's been a long time since I read "Akira," but it's certainly a series you can never forget. Although you mainly focused on Katsuhiro Otomo's story, what really impressed me as a young artist was his drawing skills. When he drew Tokyo exploding and the buildings collapsing on each other, you really believed it! I wish I had even a tenth of the artistic skills that Otomo-sensei has...