Preface!

Part of me thinks I had to pause reading and watching Blue Lock because I only ever wanted to write about Blue Lock. The part of me that thinks that reawakened today when I put Season 2 on after a few months break and was immediately smitten with this idea.

That’s the thing with good storytelling, right? You open up the book, start the show, pick up where you left off and feel like you’re right back where you belong. Like all the wires just reconnect themselves.

And yes, this is taking into account the wave of criticism that the animation for Blue Lock Season 2 is getting. Frankly, I don’t care. I’m here for the characters.

Preface over.

I’ve definitely said this before, but I’m in the business of saying things again—character is everything. Part of why manga is the best storytelling medium out there. Character is king in manga.

I mean, I’ve always been into action figures, yeah? In the 20 years before I met manga, I accumulated all of like, five figures. And one is Jar Jar Binks. Since meeting manga, I’ve reached twenty or so. I’m too lazy to count.

Just more of me overstating the power of character. But let’s graduate from a singular character to talking about how characters elevate each other, shall we?

For that, we turn to Blue Lock. As we so often do.

Before we get into Blue Lock, here’s what you need to know

300 talented high school soccer players—forwards, to be exact—have been gathered together to compete. Only one will win, and that winner will become the next starting striker of the Japanese national soccer team. With that being the primary push, the rest of the time is spent getting to know characters, relationships, and stakes. The main character, Isagi, has to learn how to both excel individually, and work with his rotating door of teammates.

And that’s all you need to know.

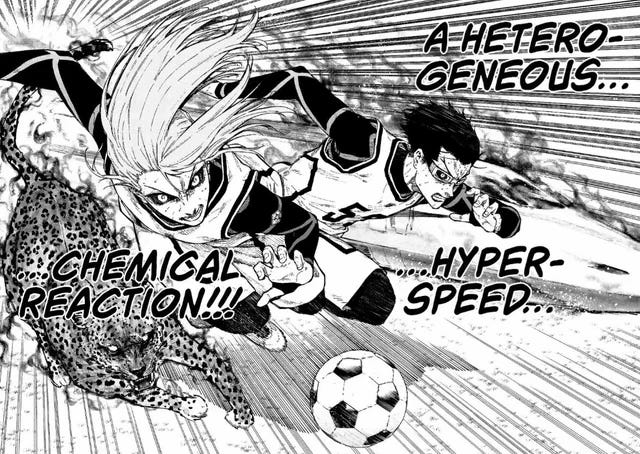

One of the main features in Blue Lock is how these young, talented soccer players learn and grow on the field. And the main way they do that is through what they call chemical reactions. Which basically means two players combining on the field, passing or shadowing or dribbling, and the end result being of a higher quality than either player is capable of producing individually.

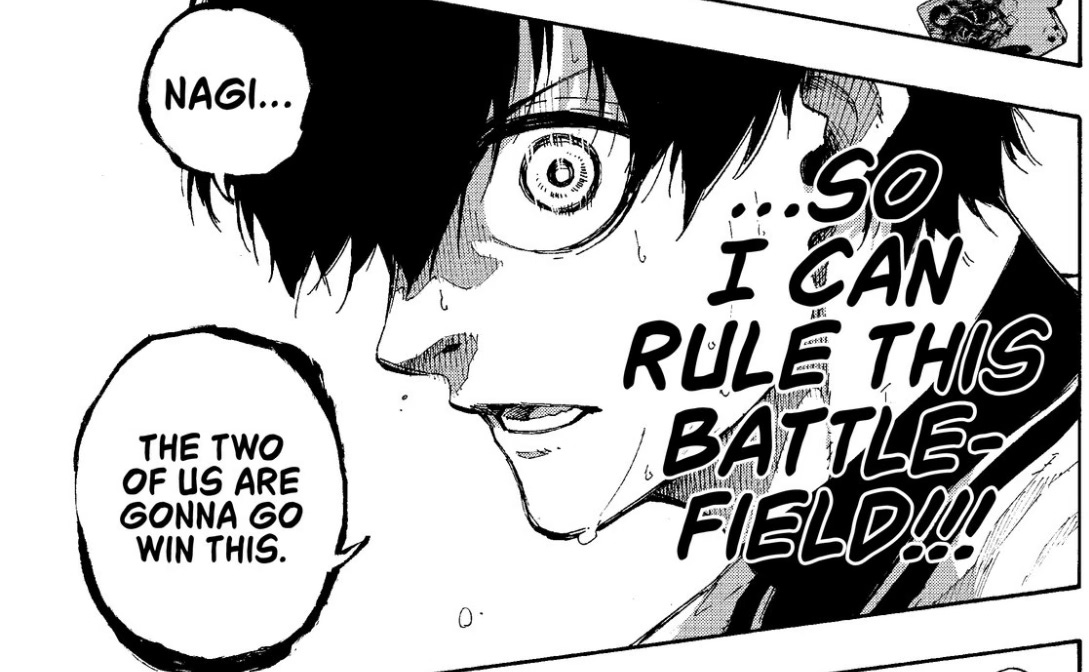

Creating chemical reactions with other players is where a lot of individual growth hinges from, but it’s also a block for when it can’t happen. When Isagi, the protagonist, couldn’t initially create a chemical reaction with my man Barou, the King, it stopped the whole team’s creative process.

Similarly, when Golden Boy Itoshi Rin couldn’t create a chemical reaction with big bully Shidou, the latter was literally tied up and put in a closet. (Don’t ask.)

Two characters with such chemistry that they essentially become a brand new character. Which actually sounds an awful lot like

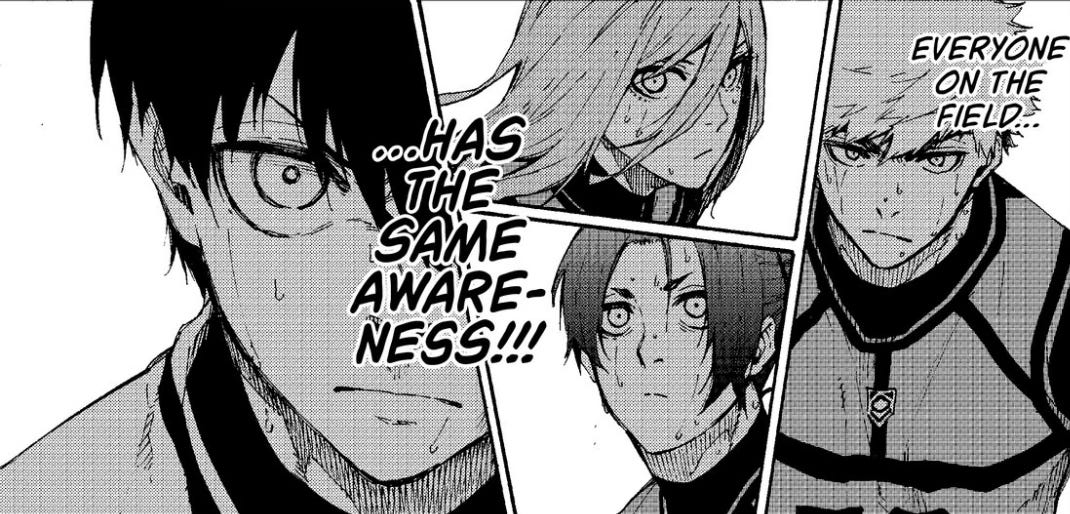

’s recent guest post about Soukoku from Bungo Stray Dogs. Chuuya and Dazai, who are strong characters on their own, become better when together.And, ideally at least, these coming-togethers make them better as individuals when they part too. That happens in Blue Lock all the time. The more Isagi creates chemical reactions with his team mates, the better he becomes as an individual. And the closer he gets with the player he created the chemical reaction with.

In the context of Blue Lock, this is an infinitely compelling source of character growth and relationship building. Everything revolves around chemical reactions on the pitch. But when we step back from Blue Lock, which I only do begrudgingly, we can see chemical reactions in characters all over the place in story telling.

A couple examples. First, from the Fantastic Beasts film series—Newt Scamander, a magizoologist, and Jacob Kowalski, a muggle baker. The Fantastic Beasts series is by no means perfect. Now, I have several gripes, in particular around the character of Creedence, who creates zero chemical reactions with any other characters. But that said, Newt and Jacob absolutely light up the screen any time they’re in a scene together. The same goes with Newt and Tina. With Jacob and Queenie. This quartet of strong characters interchange chemical reactions to make each other better. They grow together.

When Jacob shows up at Newt’s house in the start of the second film, a chemical reaction elevates both Jacob and Newt as they rekindle their friendship. Similarly—and contrarily, oddly enough—when they go to Paris to search for Tina and Queenie, Newt and Jacob are not creating a chemical reaction in the context of the story, and they keep coming up blank in their search. They’re operating too independently, not firing each other off.

Just like Isagi and Barou in Blue Lock.

Similarly, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson are like, the OG of character chemical reactions. And yes, I am primarily referring to the Guy Ritchie film series starring Robert Downey Jr. and Jude Law. Together, they are a living, breathing chemical reaction. They don’t just capture the screen, they propel the story. When they’re apart, they crave being together again, even if Watson doesn’t always admit to it. But that craving comes from how much they need each other. How, together, they are an even stronger character than as individuals.

Similarly, and contrarily, when Sherlock is with Irene Adler, not as much of a chemical reaction, if at all. They work opposite each other, rarely on the same page. It offers the perfect contrast to the true chemical reaction that is Sherlock and Watson.

There are layers to a chemical reaction between characters. How it serves the story, how it serves each individual character, how the two characters work as foils of each other, how they grow as a pairing and as individuals and, in movies at least, how well the character is played. Which, spoiler, is why Creedence makes zero chemical reactions in Fantastic Beasts.

So where do these chemical reactions come from? That’s the tough part. So much of it is just instinct, but the truly best chemical reactions come from characters who were literally made for each other. Sherlock and Watson? Legit made for each other. Newt and Jacob may not have been made for each other, but they share an adventure, an objective, they even share sisters as romantic interests. The more two character’s paths align, the more opportunities to create chemical reactions.

And sometimes it’s as simple as creating two voices that fit so well together that through banter alone, the two characters are elevated. Jude Law and RDJ as Watson and Sherlock have such great banter that, even in isolation, you can feel the effect of their chemistry.

Which, coming full circle, is what makes Blue Lock so special. Chemical reactions are happening all the time. Not just on the pitch, but off it as well. Isagi and Bachira. Isagi and Nagi. Isagi and Chigiri. Isagi and Barou. Nagi and Reo. Just to name a few. All of these chemical reactions go above and beyond the pitch. Barou and Isagi, for instance, used their chemical reaction on the pitch to blossom into a begrudging friendship/rivalry off of it.

Everything serves character, even other characters. The more you build characters to complement other characters, the more chemical reactions you’re going to have.

Very interesting analysis. I feel the author pretty much took the concept of chemistry between people and pushed it up a notch. I feel it goes to show the importance of surrounding ourselves with the right people whether it is in your professional or personal life. Companies often do not just look for someone with the right skills but also someone who will be a right "fit" for the team.

I have too many thoughts on this, so I'm just going to say YES, YES, HECK YES! and leave it there.