Preface!

I joked last time I wrote about Blue Lock that all it takes is me watching another episode or reading the next chapter to come up with a new post. Well, that’s 100% accurate, because I turned Season 2 back on for a single episode and here we are.

Blue Lock is really such a remarkable case study for its use of a simple premise and extrapolating the opportunity presented by such a simple premise to build compelling character dynamics that it stands above just about anything else out there.

Whether you have any knowledge of soccer or not, this is a special series and it is a constant inspiration for a storyteller like me. And hopefully you.

Preface over.

As part of my past and somewhat present life as a creative writing instructor, one thing I always told students who were getting ready to pitch or query was this — frame your objective. Make sure the person you’re sending this to has absolutely no doubt what the objective of your story is.

This is part of the reason I struggle with uppity literary fiction myself. The objectives are frequently so… unimportant. It’s not about that. And, again, speaking from my own personal tastes, that’s not ideal. I need to know what’s at stake, what can be gained or lost.

Perhaps another reason I love manga so much. It’s always quite clear what’s at stake. Luffy wants to be the best pirate in the world. Midoriya—sorry honey, I mean Roy—wants to be the best hero in the world. Laios wants to save his sister.

And Isagi, Bachira, Barou and the whole crew in Blue Lock want to be the best striker in the world. So how does a series like Blue Lock take a simple objective and make it compelling?

Glad you asked.

Before we get into Blue Lock, here’s what you need to know.

300 of Japan’s top high school strikers have been rounded up and put in Blue Lock, a competition to whittle the striker crop down to one and create a masterclass striker to lead the Japanese national team. But becoming the best striker is an objective that looks different for different players. All of them need to grow in some way, and that’s where Blue Lock really shines.

And that’s all you need to know.

As I covered in previous pieces about Blue Lock, including the first ever piece here at MangaCraft, one thing Blue Lock does to rise above is giving everyone the same, simple objective. You never have to check in on that objective or vary it, because that’s unnecessary, and it also opens up so much more room for other storytelling elements.

And that’s where things get fun, because while the objective is a firm goal post, it doesn’t move, where every character attacks that goal from is different, and Blue Lock makes the most of showcasing this for amplified character dynamics.

Two examples.

Isagi and Rin Itoshi

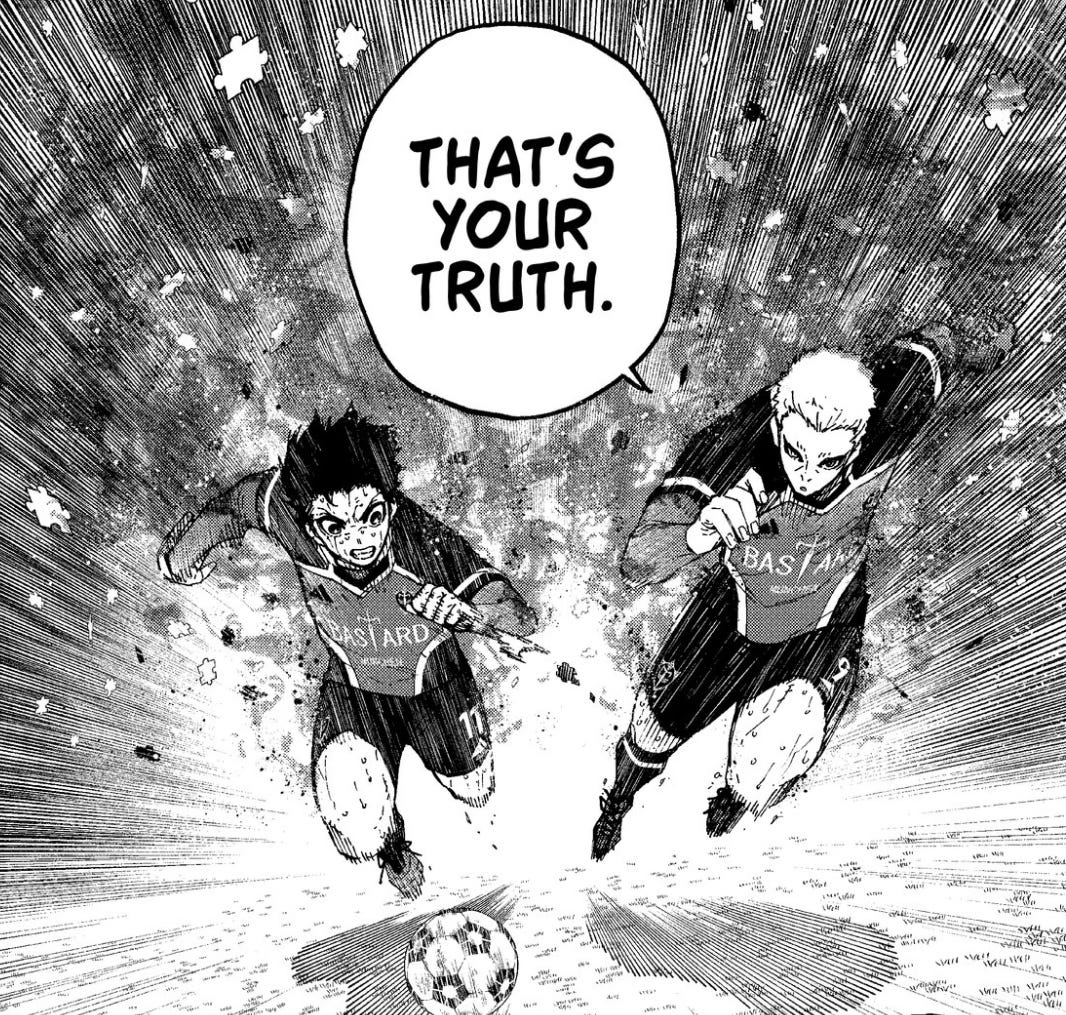

Barou and Shidou

With Isagi and Rin, the two are very similar in terms of play style. They aren’t traditional strikers, but moreso creative. Rin is more ruthless than Isagi, but Isagi is more understanding than Rin. In a sense, Rin is an extreme version of Isagi.

With Barou and Shidou, it’s much the same. Shidou is an extreme version of Barou. He’s even more egotistical, more cruel, more ruthless. But in a way, Shidou is what Barou thinks he himself is. The same way Rin is who Isagi thinks he wants to be.

Which again circles back to how this objective serves the story so well. Think of the objective, “to be the best striker in the world,” as the center of a circle and these 300 high schoolers all starting at different points outside the circle. They have to grow and improve to move closer to that bullseye.

And by using a character like Rin, we can see what Isagi is aiming for. But Rin also needs to be more like Isagi, in a way, even if he will never acknowledge that. So in a since, characters like Rin and Shidou act like extreme versions of what more likable characters are both grappling against, and aspiring towards.

Objectives look different to different characters. Yes, the best striker in the world is going to need a serious ego, which Rin and Shidou have, but they also can’t be so selfish as to not be conducive to a team’s overall operations. It’s an ebb and flow. No striker can win Blue Lock with the same skills and personality that they entered it with. Everyone has to grow. Some grow in the wrong direction, like Shidou. He’s getting more and more brutish to the point that he is kicked out of Blue Lock.

But Barou and Isagi have to grow into their hardened edge more, without going too far. It’s such an inexact science and that’s what’s so exciting.

I always like to relate manga-related discussions to mainstream examples, so I’m going to do my best here with—surprise!—Lord of the Rings.

Let’s think about the Council of Elrond. One ring in the center of a circle of dignitaries from all the corners of the free world. One objective—deciding what to do with that ring. Boromir wants to use it. Elrond wants it out of his city. Gimli tries to smash it. Legolas buddies up with Aragorn. Frodo wins out when he resolves to take the ring himself.

So many conflicting viewpoints all aimed at a singular objective. So many ideas on how to achieve that objective.

But even with that, the objective is not set in stone. In Blue Lock, it is. And that’s why it works so well. At the Council of Elrond, the questions are what the next objective regarding the ring will be and who will carry it out. In Blue Lock, there is no next objective. All that matters is who will achieve it and how.

Which, in the simplest terms, makes this a very cut-and-dry point A to point B objective kind of plot, with each character’s point A being vastly different, but their point B being the exact same.

And again, this works so much better by having characters with such extreme personalities that we can see individual traits in each one of them that would indeed lead to them being the best striker in the world. But by the same token, no character has all the pieces yet.

Another thing, and this goes back to thinking of this objective like a dot in the middle of a circle instead of a finish line at the end of a race. Compare this to My Hero Academia, where being “the No. 1 hero” is a bit more fluid. There aren’t necessarily set traits or achievements to becoming this. You are just ranked as the most effective hero at solving problems. That can involve power, ingenuity, resourcefulness, goodness, and so much more, but it’s a malleable achievement.

For Blue Lock, the end goal is cut and dry, and while there is some wiggle room to achieving that end goal, overall, it comes down to very specific bullet points: ego, ruthlessness, goal scoring, and overall talent.

The whole idea for this article came from watching the Japan U21 arc, where Rin, Isagi, Barou and Shidou are center stage. Isagi in Rin’s shadow, Barou in Shidou’s. It’s really masterful the way these dynamics allow us to think about what it would look like for someone like Isagi or Barou to win Blue Lock. Or, for that matter, Nagi or Bachira or any one of the guys. What do they need to do in order to win? What would their version of the best striker in the world look like, and how much room is there for variation?

In closing, let’s think about Isagi. Part of being a striker is having an ego. Shidou, Barou and Rin have one in abundance. Isagi, not so much. So as readers, how much do we want to see the Isagi we love become more selfish and egotistical. Isn’t that what he needs in order to advance? Or is there an Isagi version of being the best striker in the world that avoids that? Because honestly, I don’t want Isagi to become like Rin.

And if Isagi does shed his goodwill for malevolent ego, is that really achieving the objective. Ah! Perhaps the objective of Blue Lock is not so simple after all!

Isn’t storytelling fun?

This is an AMAZING read!! I love Blue Lock and think you made some compelling points. #1 fan!!!

Ahhhh I’ve never clicked on something so fast in my life. I have ADORED Blue Lock since it first started airing. I’m not sure how caught up to the manga release you are as of now, but I think Isagi’s growth lately has been such a blast to watch unfold. Like you said, the uniformity of the goal provides so much room for the different ideologies on how to get there to clash with each other, and the joy of watching these characters all grow into their niche egos and styles is the best part. Loved this, great read!