Blue Lock: The Power of a Unified Objective

When every character wants the same thing, oh, the fun you can have.

Preface!

As of this very sentence, the background on my computer desktop is Team Z from Blue Lock. I’m all caught up on the series and watching it now too. I’m smitten. I haven’t felt so engrossed in a series since Jujutsu Kaisen and, not gonna lie, I’m kinda falling out of love with Jujutsu Kaisen lately. I put off Blue Lock for so long, thinking that I’d have no interest in a sports manga. Not sure why, seeing as how I spent ten years as a soccer writer or anything. Maybe I was scared how much I’d like it?

Anyway, Blue Lock is my everything right now. It’s a blend of massive, manga-sized stakes and the psychology of the beautiful game. I could sit here and gush (which I will inevitably do anyway) instead of getting to the point, but…

Preface over!

One thing that any person or character needs is an objective. That’s what a story is, right? It’s the chasing and clashing of objectives, when what one character wants runs into what another character wants. No matter the medium, you won’t find a story that isn’t built on objectives. With manga, those objectives are often shifting and twisting and contorting. Different seasons give us different objectives, all built on one central objective that the protagonist is after.

But what about when everyone you’re rooting for wants the same thing? In Blue Lock, every single main character wants the same thing—to be the one player chosen from the Blue Lock experiment to be the best striker in the world. That shared objective is established from essentially the first chapter. Everyone wants it.

Think about that for a second. When is the last time you read/watched a story where you didn’t need to check in on the moving goal posts of various objectives? I think of Jujutsu Kaisen as a comparison. Two conflicting factions, but there are factions within factions, characters die and objectives change. Same goes with Chainsaw Man. Denji’s objectives are constantly shifting and reconfiguring, never mind the amorphous cast of characters that come and go and reincarnate with different goals. That’s what each “arc” in a manga is all about. Each arc reshapes the primary objective. Each arc, we, as readers, have to reground ourselves in what’s at stake this time for each character. That’s why some arcs fall flat in manga. The amount of times I’ve had a friend recommend a manga or anime with the caveat of “you need to get to the third arc/chapter/season for it to really work, and skip the fifth arc, it’s garbage.”

The same happens in mainstream stories. Star Wars for instance—first it’s the Trade Federation, then the Empire, then the First Order. Enemies shifting, alliances changing, objectives moving about. As consumers, we always need to know what’s at stake, right? Once our characters catch or solve or defeat that objective, it becomes something else, and that something else needs to be clear and established. There’s nothing wrong with that. That’s how stories work. Stories reshape, characters learn and grow. As readers, we cling to hope that this next story arc doesn’t turn out like the First Order story arc. Again, that’s just how stories work.

That’s not how Blue Lock works.

In Blue Lock, every single character wants the exact same thing. Now, the snap impulse may be to think, “well that sounds boring.” Oh, how wrong you are, random snap impulse. Because with such a clear and simple shared objective, as readers, we never have to reorient with what’s at stake or what we’re doing here. In a sense, that entire story element just lives in the background, never shifting, never changing, never moving. It could slightly alter forms or introduce new knots, but never to the point that it alters the plot. Which means that as the storytellers, writer Muneyuki Kaneshiro and illustrator Yusuke Nomura can take all that extra space that isn’t spent reorienting on the new objectives and apply it to other elements.

Namely, character and relationship building.

Blue Lock juggles a lot of characters, each with pros and cons, traits, flaws, wants and needs. Just to make a point, I’m going to list every character that you can/will have a stake in, in no particular order: Isagi, Bachira, Kunigami, Chigiri, Gagamaru, Igarashi, Barou, Reo, Nagi, Rin, Ego, Karasu, Aiku, Hiori, Nanase, Shido, Aryu, Otoya, Raichi, Zantetsu, Niko—could I go on? Yes, I could, and there’s more to come. That may just be a list of names to you (if it isn’t, hmu let’s be friends). But to me, that’s a bunch of people. Choose any two and I could tell you about the shape of their relationship and how it’s grown over the course of the story.

Now, granted, manga usually have big character casts. That’s not out of the ordinary. My Hero Academia is much similar in cast to Blue Lock, with a class full of characters, any of which could be a favorite and any of which has a relationship with any other. It’s probably the main thing that makes it so popular. But again, that full likable cast is engaged in a plot that shifts and twists and turns with multiple factions and complex conflict points. Each arc presents its own challenges and so many characters are after different things.

Not just that, but big cast mangas also have a core cast. Blue Lock’s core cast is arguably that entire list, minus maybe a name or two. Each of those characters is fleshed out, has an established back story, their own motivation for being here, their own personality traits and their own growth.

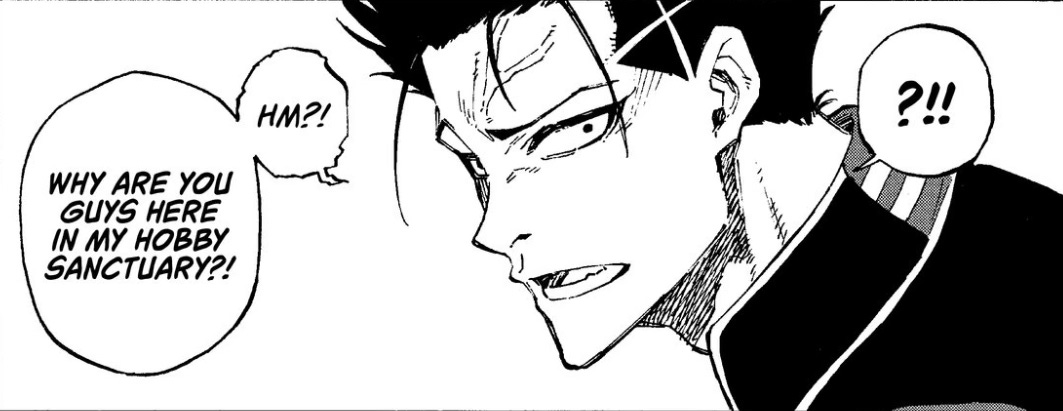

Manga is unparalleled in character growth and sure, a big reason why is because of how much room these series have to flesh out true arcs. But Blue Lock is unparalleled in an unparalleled medium. I mean, I straight up hated Barou when he first hit the page. Now I’ve preordered a figure of him for my desk (I’m fundamentally against the concept of preordering, fyi) and arguably my favorite out-of-context manga panel…

…is him.

One more? One more…

Okay, Barou aside, How do they do it?

That’s exactly my point. By building an entire plot out of one shared objective, and using the extra space not used on dumping exposition to create full characters. Characters who ascend past their “one trait” and become something more. Manga always tends to introduce new characters with their one thing, and Blue Lock does the same. Nagi is lazy. Barou is selfish. Bachira is weird. Yada yada. While those one traits still form each character’s respective cornerstones, they grow beyond that singular stone and become entire buildings of complex skills and emotions that mix and match with everyone else’s buildings to form a gorgeous neighborhood of interconnected brownstones. A neighborhood that stands alongside the most luxurious neighborhoods in storytelling.

That metaphor worked better than I expected.

There are plenty of other manga that do something similar to Blue Lock. Keyword being ‘similar’. In My Hero Academia, Midoriya wants to be the No. 1 hero. So do others in his class, though perhaps not explicitly. The difference is different characters outside of Class 1-A want different things. There are warring factions, working heroes, so on and so forth.

Same goes with One Piece, though One Piece is even more unified than My Hero Academia. Luffy, along with a ton of other characters, wants to be the world’s best pirate. Simple, clean, concise objective not unlike Blue Lock. But other characters want other things. Warring factions, clashing pirate crews, multiple groupings of this or that, it’s complex.

Blue Lock is different. Aside from the brief cutaways to the Japanese Football Association folks, Blue Lock is all characters, one goal (pun intended). Which is the whole point behind me putting this many words into explaining why it works so well.

Another, related thing that makes Blue Lock such a shining beacon of character is the dichotomy of having characters competing for the same thing, yet still becoming friends. So while they’re duking it out in a cutthroat competition that will literally define (or ruin) their lives, they are also forming friendships and building bonds, each of which feels wholly unique to the characters involved.

The point is, you cannot have this level of character building across so many characters and relationships under normal circumstances. Even a story like One Piece, which has over a thousand chapters, still operates with a core of, what, seven characters? (I’m only on chapter 580, forgive me.) The relationships they share are exceptional, and they build tertiary relationships as well. But Blue Lock is only 200ish chapters in (as of writing) and the sheer diversity of friendships, frenemies, straight-up enemies, rivals, etc. is expansive, impressive, and growing, each one just as impressive as the last.

So, I’ve gushed a lot about Blue Lock here, and for good cause. But the takeaway is simple. They did something very easy—a shared objective—and had a blast in all the free space it created in lieu of resetting and reshuffling the plot.

Where does Blue Lock go from here? To the freaking moon, for all I care, as long as Isagi, Bachira, Chigiri, Kunigami, Nagi, Ren, and, of course, Barou are along for the ride. Maybe the objective does change, it probably will. I can’t imagine we’ll spend the entire series in this competitive stage. But that’s fine by me, because it’s built such strong relationships among such incredible characters that the hard work is done. And it was done through the power of a shared objective.

To all you creative writers: what are your characters’ objectives? Can they be simplified?

To all you manga lovers: how much do you love Blue Lock, on a scale of 1 to Barou?