Drifting Classroom: Setting A Precedent

Sometimes we just want to know what a story is capable of.

Preface!

Ever since reading Junji Ito’s memoir Uncanny, I’ve been trekking through the list of horror manga that inspired him. Naturally, that led me to Kazuo Umezz, someone who I’ve only ever known about from a distance, always buried in my TBR, never rising to the top.

It’s embarrassing to admit, but I didn’t know how seminal Umezz is to understanding manga as a whole, and horror as a whole too. I started with My Name Is Shingot and reveled in how subtly the horror is being set up.

And then I picked up Drifting Classroom thanks to the insistence of a good friend in the manga industry (Hi Mark!), and now I’m thoroughly obsessed with Umezz. I just want it all.

Also, I find the way he draws children hilarious. I don’t know why. Their faces just make me cackle.

Anyway.

Preface over.

There’s a moment in the John Wick series that changed my perception of storytelling forever. You see, there’s an old saying in storytelling that the dog cannot die. I used to work for a literary agent who would straight up decline any story where a dog died. Sometimes she’d even reach out to the author of a book involving a dog to ensure that the dog didn’t die. It was a pretty widespread practice. There were rare, rare exceptions, but seriously—the dog cannot die.

So in John Wick, when his wife gets killed, okay, that sucks, but we’ve seen it before. It sets up a nice revenge arc.

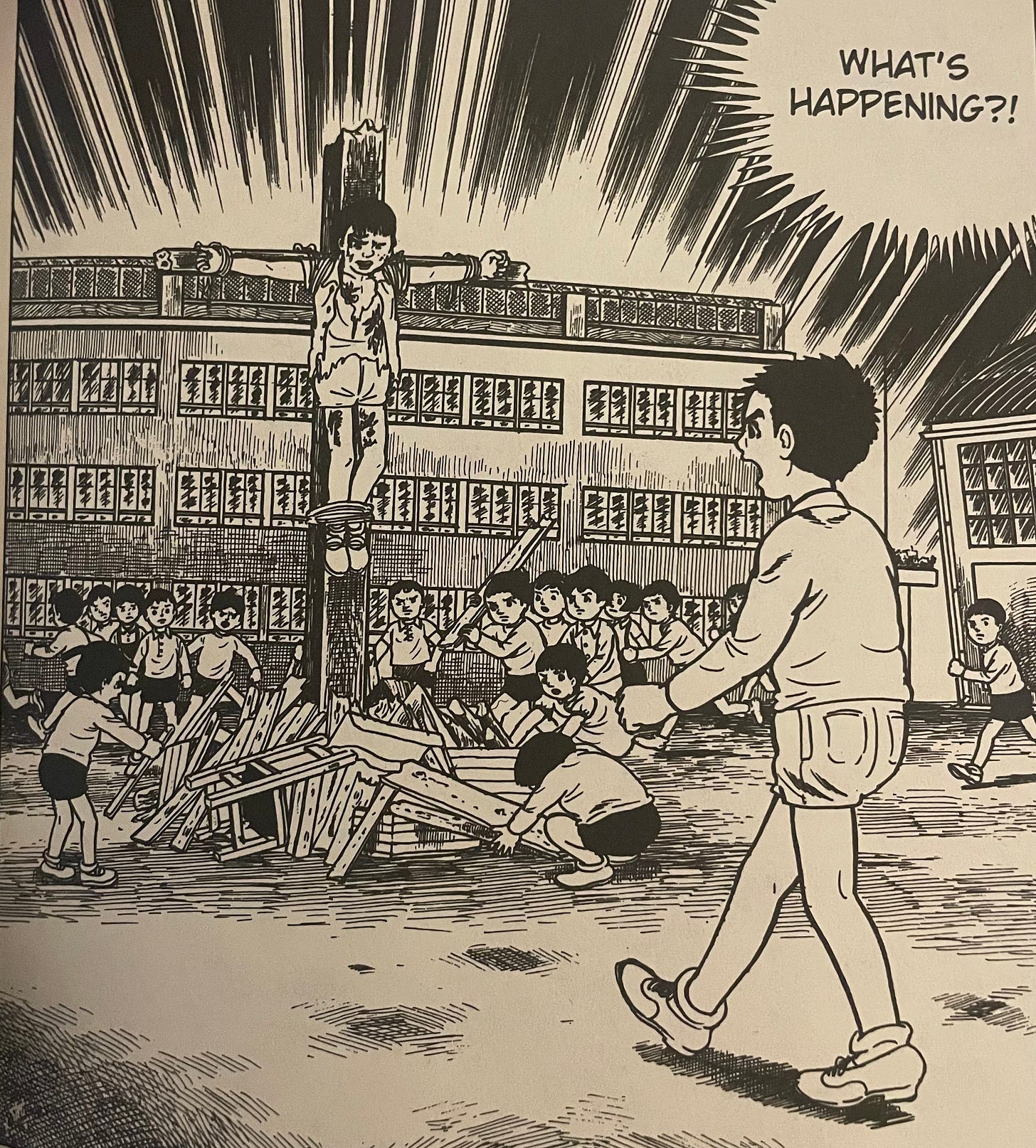

When the bad guys kill his dog though? That sets a precedent. That elevates the conflict to a plain rarely trodden by storytelling shoes. And the effect is immediate. If they can kill the dog, what can’t they do? If Kazuo Umezz can have first graders crucify a sixth grader, what can’t he do?

What I’m about to cover here is the exact opposite of what I talked about in a previous post pertaining to the masterful way The Summer Hikaru Died wields subtlety. And honestly, it’s the exact opposite of the way My Name Is Shingot is subtle too. Because Drifting Classroom is not subtle. In a good way.

Before we get into Drifting Classroom, here’s what you need to know.

Yamato Elementary School has disappeared from town, taking all the children and staff with it. The school ends up in a desolate wasteland future. In the wake of this disaster, there is one intense power grab after another for who controls the 826 displaced folks of Yamato Elementary. People die. Lots of people die. Monsters arise. It’s pure chaos. Through it all, our anchor, Sho, is the hero the school needs.

And that’s all you need to know.

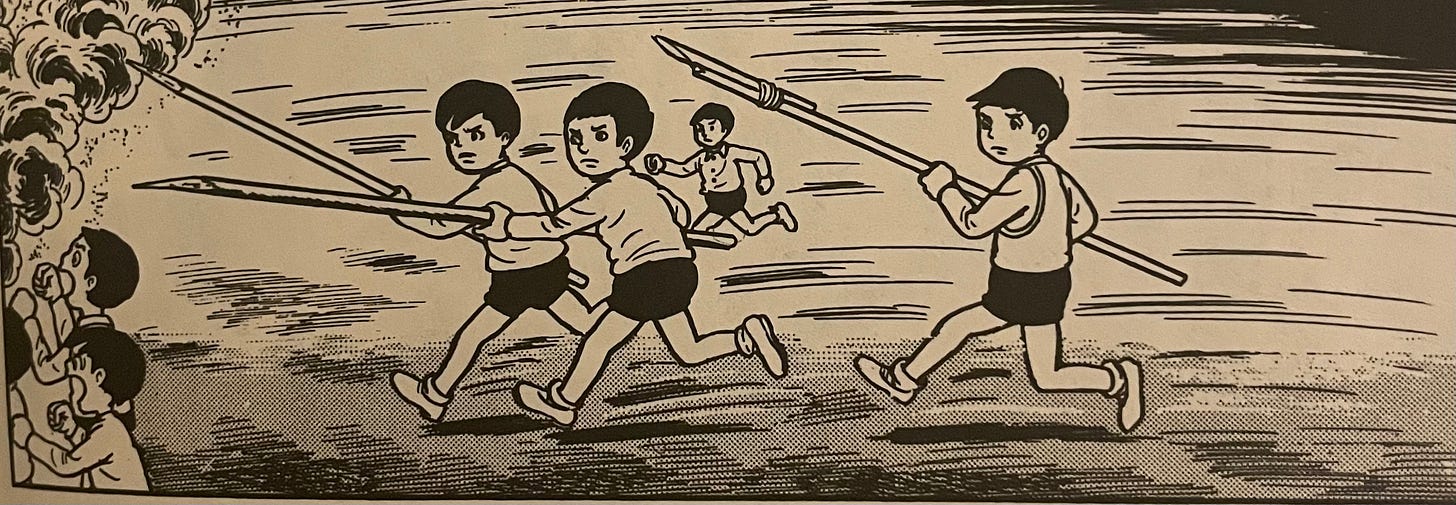

Mere pages into the upheaval following the school’s time travel, kids have gone fully unhinged trying to vie for control from each other, included but not limited to viciously attacking each other. A few teachers strangle each other. A psychotic and potentially homicidal lunchroom worker is locked in a locker. And best of all—a bunch of first graders have put a sixth grader up on a cross and plan to burn him alive. You know, the usual. Just casual, everyday middle school destruction multiplied by like, a million.

There’s no “too far” for Drifting Classroom. And that precedent comes from something you just don’t see in manga, or in storytelling in general—kids going full militant, quite literally fighting each other to the death. It feels weird to even type. And by weird, I mean wrong. But it serves a narrative purpose.

When I was first finding my way into middle grade publishing, there was one book in particular that completely rocked my understanding of the genre. The Night Gardener, by Jonathan Auxier. I was operating under preconceived notions that no one could die in middle grade, at least not violently.

Lo and behold, more than one person dies in The Night Gardener, and just like that, my understanding of what a genre could do expanded massively. Now, to be fair, very, very rarely do people die in middle grade, let alone violently, but The Night Gardener set a precedent and I’ll never shake it off. People could die.

The same applies to Drifting Classroom. Knowing that this series has a close parallel to Lord of the Flies, you’d think that maybe I’d have expected it to be, well, permissible for kids to kill each other, since they do in Lord of the Flies too. But the difference is Lord of the Flies is text. It’s one thing to read about it, it’s another thing to see it, and Umezz may be coy in certain scenes, but he isn’t always.

It sets a precedent. These kids aren’t safe, not just from the world around them, but from each other. They’re savage, at times. They aren’t protected by plot armor. In the same way that I never expected anyone to die in My Hero Academia because, well, no one ever died, I expect more people—more kids, dare I say—to meet untimely ends in Drifting Classroom, which in turn makes me cling harder to my favorites and hope they aren’t on the chopping block.

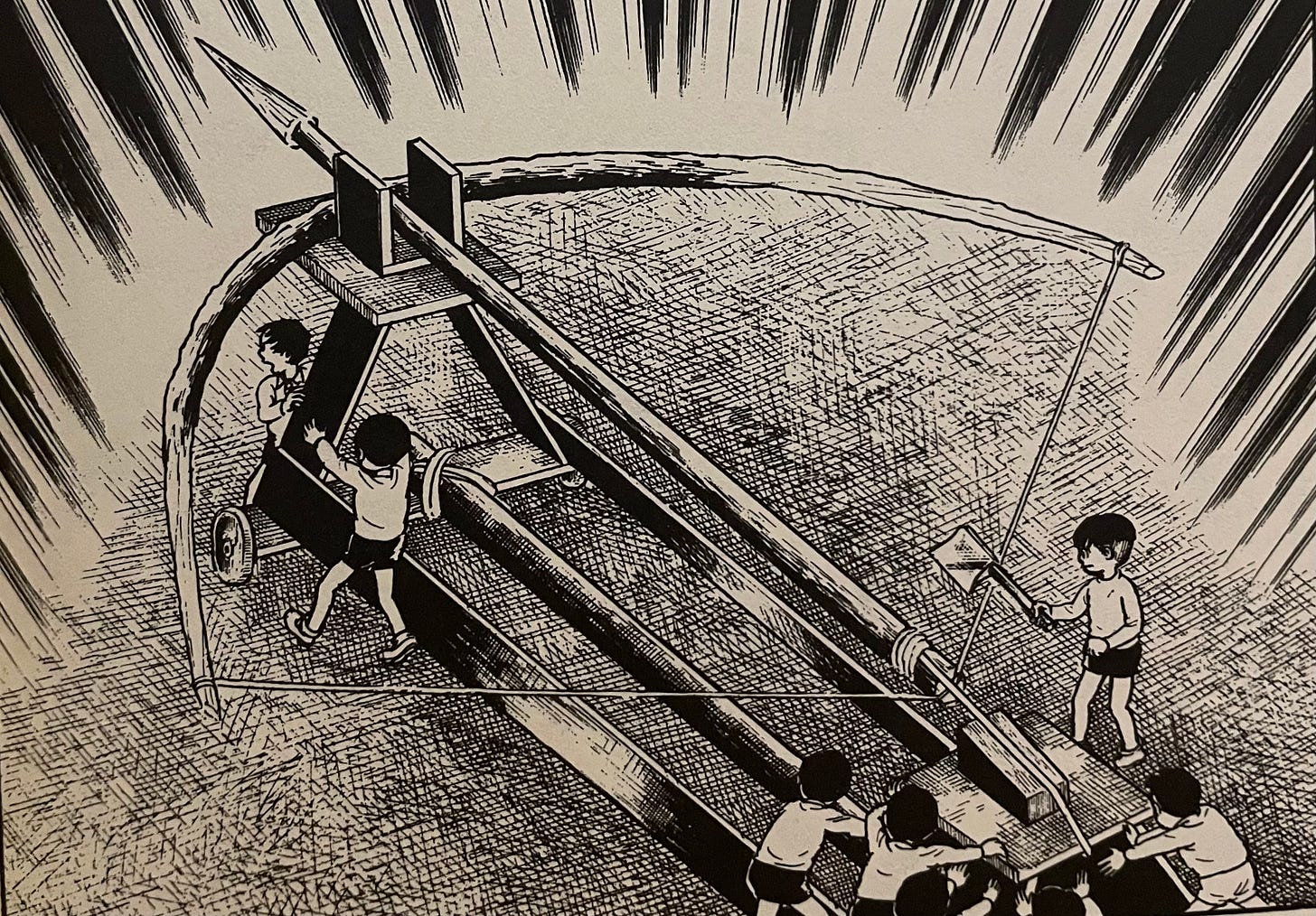

All told, that’s a great place to have your readers. We cling harder to characters when they could meet their end at any moment. I feel vulnerable as a reader knowing that I could be rocked by another death. Similarly, I feel energized by not knowing how or when the story will elevate the tension through another bizarre and unexpected precedent. For instance, did I foresee a bunch of sixth graders constructing and operating a medieval arbalest to fight a giant mutant centipede? Sure didn’t.

Where this really all pays off can also be demonstrated by Drifting Classroom. There comes a chapter where Sho, our fearless sixth grade hero, is presumed eaten by the aforementioned giant mutant centipede. He is out of the story for a good chapter or so and throughout that chapter, I was fully contending with the possibility that Sho was actually dead. I even skipped ahead to see if he came back because I need to know these things.

That only works if the precedent has been set that these characters—kids, no less—can die. So what is stopping Sho, a kid, from dying?

It’s not easy to set a precedent, but they don’t all have to be monumental “dog death” precedents. Those are just the easiest examples to grasp. The same principle can be applied in just about any genre. In humor, for instance, some jokes push a precedence for what the humor barometer in a particular story is. In science fiction, you can set precedence in the size of the universe, the technology of the spaceship, etc. If you’re going hard science fiction and defining the technology of the hyper drive generator, you better recognize that sets a precedent for other technology in the series to be equally well described.

And that’s another thing that must be mentioned—if you set the precedent, you have to keep challenging it, either meeting it or pushing it. Drifting Classroom continues to push further and further from that initial precedent-setting moment.

A counter example, and then I’ll shut up about setting precedents. One of my favorite movies of recent times is The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, starring the dynamic duo of Nicolas Cage and Pedro Pascal. The movie is hilarious and remarkably well written, but there’s one joke in the movie that sets a false precedent. I’ll spare you the full run-down of context, but in short, Nicolas Cage ends up being taken by the CIA and one of the agents snaps at him. The other agent apologizes and says that her colleague is upset because he just found out that his wife’s been sleeping with his dad.

Whether you find that funny or not, it’s not the right humor for this movie. That’s Seth Rogen movie humor, not the quippy, story-driven humor of The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, and it’s the only joke that goes that way. As such, I find myself dreading the joke every time I rewatch the movie because it’s the only part in the movie that feels out of place. Unsurprisingly, no other joke falls in the same category.

In the same way, it would have been weird for a kid to fall to his demise off the school roof in the opening chapters of Drifting Classroom, and then no one else dies for the duration of the story. It wouldn’t make sense. It would feel out of place.

Drifting Classroom pushes and pushes into bizarre and unexpected territory. It’s a great example of how, once you start pushing the envelope, you can keep pushing it further and further, to deadly, yet delightful effect.

Hey creatives—you should be aware of the limits your story pushes, or the precedent that your readers expect. Whatever genre you’re in, whether you actively think about it or not, you set expectations in your opening chapters as to what your story is capable of. Look at your opening chapters—what are you hoping your readers will take away from them? Do you follow through on those expectations later on? No exercise use this time, just something to look for.

Hey, fans of Drifting Classroom—what surprised you the most? For me, it was the giant arbalest that randomly appears and then is never mentioned again. How did they build that?!

Oh hi Josh. How on earth do you write so much and so well? I spend like 3 to 6 hours on pieces like this!

I was largely unaware of Kazuo Umezz’s work until his death, unfortunately. Thanks for bringing Drifting Classroom to my attention! Adding it to the list. 😊