Preface.

Me and high fantasy usually don’t get along that well, but even as I write that line, I’m asking myself—really? That doesn’t sound right. I thought I loved high fantasy, but I don’t read it a lot beyond Lord of the Rings. And The Witcher. And… maybe some others. Narnia.

Anyway, somewhere on social media, I saw someone mention that Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End was well written and, yeah, that’s not always a given in manga, especially in translation. So I dug in, reading it in tandem with Dandadan, thoroughly expecting Dandadan to win out but… the battle is ongoing.

Preface over.

Back in circa 2013, I hosted a scary movie night every Tuesday. One Tuesday, we rented a movie called The Innkeeper which was, by all accounts, a terrible movie. For about an hour and fifteen minutes, nothing happened. Some piano keys jingled without being touched, some people talked. Eh.

Then, for the last fifteen minutes—sheer bedlam. So much so that even now, having not seen the movie in over ten years, I vividly remember how the dead guy appeared over the lady’s shoulder and pushed her down the basement stairs. Just a mess of chaos and destruction, right there at the end of all things, right when you least expected it.

That movie was incredibly disproportionate. Such that the one scary moment, which honestly probably wasn’t even that scary, lingered hardcore because of the false sense of security I’d been lured into. It’s like that old adage that you need to get a boxer to lower their gloves before you throw a punch. The Innkeeper got me to take off my gloves entirely, and then it threw what was probably a weak jab, but hey, I wasn’t ready for it, so it hurt.

Every story has proportions. How much time is spent on character, plot, humor, tension, romance, silliness, so on and so forth. It’s like a bunch of pieces that all have to fit together to form a complete picture, but the creator is determining the size and shape of the pieces.

For most manga, the proportions are skewed to favor the genre they're in. As a high fantasy, the assumption is—battles! Battle sequences are given so much time and space in similar stories. Entire volumes are given to duels and showdowns. Everyone on social media gushes over what the best battles of all time are. It’s a whole thing.

Enter Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End. The story of an elf mage after her and her party defeat a demon king, and what she does, as the title suggests, beyond that journey’s end. This story is all about the passage of time, and what that looks like to an elf who is basically immortal.

Lo and behold, what that anonymous person said on social media was correct—this is really well written, with dialogue that resonates as human, meaningful and subtly hilarious. But the one thing that really stands out about this series is that the proportionality is—and this is a technical term—completely whack. In the same way that The Innkeepers was, but more sustained and ongoing. And also way better.

The thing with Frieren is the time management is intentional and it is expertly done. Months pass in the span of two panels, battles resolve in a page. It’s unlike any other manga with any sort of active conflict. The below panel…

…is the entirely of a “boss battle.” Zip, dead. That’s it. Another example…

That’s an entire battle sequence. Two characters fighting a horde of giant wolves. Not much to see, right?

Not just that, but Frieren pulled a similar move as The Innkeeper in the early going. For the first two volumes, the titular character was just kinda wandering around. It was immensely entertaining, because the narrative quality is so strong, but by all accounts, nothing happened. Nothing of note. A few twinkling piano keys.

I didn’t know what to think. Maybe it was something of a cozy fantasy, which is all the rage these days in publishing. And I still think it may fit that category. When conflict or battles happened, they didn’t happen happen. They were inferred. Same with “action” like clearing a landslide. They didn’t happen, we just saw the bookends—the problem being presented and the solution that came after.

This all hit home in the first major battle. Frieren, Fern and Stark—the good guys—square off against the demons Lugnar, Linie and Aura—the bad guys. This is it, I thought, the moment everything I thought I knew about the whack proportionality goes out the window. The moment it becomes like everything else. Which still would have worked, because I love these characters, but surely, surely we’re about to get a two volume battle royale.

Nope. Sure, there was active battling, but they were over before I could turn the page. Literally. Realistic, perhaps, since if you sever about 15% of someone’s body, they’re going to die pretty quickly.

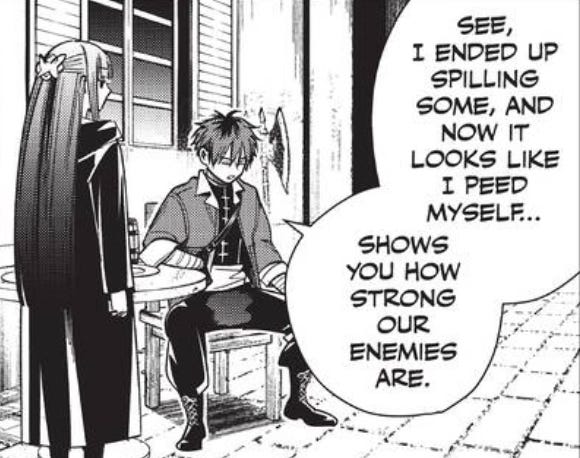

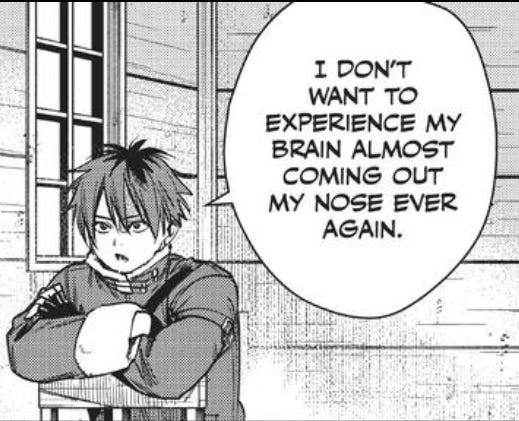

Unlike in other manga, where characters suffer seventy-two gunshot wounds, a hundred and twelve lacerations, three complete and two partial amputations, internal bleeding, a shattered cranium and a complete loss of bodily function, then have a cup of soup and are ready for round two by lunch time, Frieren took a different approach.

So the question is, what does Frieren get out of this conscious choice to skew away from action? Similar to what Blue Lock gets from a unified objective, though Blue Lock’s takeaway is more a built-in byproduct while Frieren’s is absolutely more intentional.

It gets more room to build character.

Creatively, it’s really difficult to balance your story. How much time you spend in one moment or another. An old writing colleague, or teacher, or maybe a famous author, I don’t know, once said that it’s what you don’t write that is more important than what you do write. By sacrificing the action—essentially not writing it—the focus shifts entirely off of it and the spotlight rests on character.

But the caveat to that is that for this blueprint to work, the characters have to be extra strong and their dialogue has to be exponentially more entertaining. All in the name of holding the spotlight. As soon as readers start getting bored with what’s in the spotlight, they’re going to want it to go elsewhere. It’s a lot easier to be dubbed “entertaining” when you have two superpowered warriors exchanging roundhouse kicks in the bowels of hell than it is to be entertaining with people just talking. Frieren is just talking with the occasional sucker punch battle.

It’s not just the dialogue that works, though that’s a tremendous starting point. Frieren gives us characters we care about, with personality, with distinctness. Each major character—and there are a good amount—has their own traits. Another gold star for Frieren.

But wait, there’s more!

As if making the challenge even more difficult, the sense of humor in Frieren is so subtle. It’s not Monkey D. Luffy screaming in your face or the heavy-handed comedic relief that you’ll find in singular characters like Inosuke and Zenitsu in Demon Slayer or the whole damn cast in Dandadan. No, in Frieren, the facial expressions are almost exclusively deadpan. The humor is situational and quiet. Some examples!

Yeeeeaah, they’re all Stark, because Stark is the best. That said, the humor doesn’t begin or end with him. Since each character is distinct, they each carry their own humor and, unsurprisingly, it’s all just as effective.

It takes a lot for me to gush this much about a manga, but that’s because, in a crowded, crowded manga landscape, Frieren has two things you don’t find often—it’s very unique, and it’s very well written. Even in translation, which is crucial for this series to work, the language and word choice is so effective that there’s no missed beats.

So, clearly I’ve descended into a gushing fest, but I’m curtailing that now. Reluctantly.

What Frieren shows us is that there is no right answer to the proportions of a story, manga or otherwise. It’s a reminder that if you know you do one element better than another, then you can skew to that one, even heavily, but—and there’s always a sizable ‘but’—the extra dose of your preferred element absolutely must justify why it’s getting so much more attention. Otherwise you’re not doing yourself or your story any favors.

Frieren gets creative with its whack proportions, outright skipping battles and action sequences. It’s almost like they’re showing off just how strong the other elements are. You can do that too. Stories are supposed to be fun, right?

For creative writers: what is your story’s biggest strength, and how can you intentionally build around that?

For Frieren fans: Stark is the best, yeah? Anyone disagree?