Trigger Warning! I will be sharing a series of panels (at the very end) with a gun in a school environment.

Preface.

I had seen The Darwin Incident on shelves many, many times, but I always passed it up for one reason—the main character creeped me out visually. He made me uncomfortable. I just didn’t want to look at him.

It was the eyes.

However, after talking to a friend (Hi, Ryan!) about The Darwin Incident, his insistence convinced me to give it a chance. He knows manga better than I do, and when he recommends something, I’m in. (Thanks, Ryan!)

It’s been awhile since I binged a manga. Just powered through all it had in the span of a couple of days. I did that with The Darwin Incident. Partly because the small-town Missouri setting reminded me why I moved to New York City, and partly—mostly, rather—because Charlie, the protagonist that still gives me the willies to look at, is impossible to really figure out.

Which is the whole point.

And also not really the point.

Preface over!

Unreliable narrators were all the rage when Gone Girl was published in 2012. Suddenly the entire mystery/thriller section was just full of all these characters that you couldn’t trust. And that was the whole shtick, obviously. Gives readers a whole new layer to read into a work.

I never read those books. But the idea of an unreliable narrator stuck with me, and when I officially switched all my prose writing to first person, I began to see that, accidentally, I was writing unreliable narrators myself. Because, technically, every first person narrator is unreliable.

We only see the world through their eyes. How do we know what’s true?

There’s a writing phrase I only learned recently—psychic distance. Now, I’m not big on hyper-fixating on the mechanics of storytelling. I’m definitely a trust-my-instincts kind of writer. But psychic distance is fun to think about. It’s how close you bring the reader to the story. Are they playing in the snow, feeling the cold on their finger tips, or are they seeing the world from a bird’s eye view, reporting what happens?

Long-winded intro aside, it’s more complicated to think about perspective in visual storytelling. There aren’t any first-person-camera comics or manga. Moments? Sure, but we’re rarely in the head of the protagonist, barring first-person narration, which is generally pretty straightforward.

As such, not a whole lot of unreliable narrators floating around in the visual space.

Then I met The Darwin Incident, which centers on Charlie, a “Humanzee.” He’s half human and half chimpanzee. He’s not an unreliable narrator in the traditional sense, but he’s very unreliable emotionally.

Since he’s part chimp, he doesn’t have the same emotional capacity as humans, which makes him this really fascinating sandbox of unreliability. We don’t know how he really feels about things, or how he engages with those things. We really don’t even know his morality because his face doesn’t show expression and he has emotional complexities that, as readers, we’ll never understand.

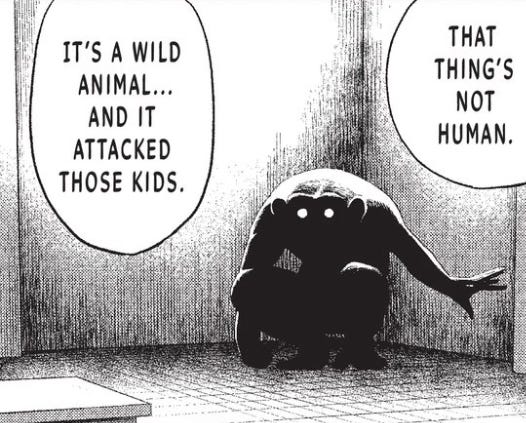

It makes for the perfect vessel for this story. And the art lends itself well to the unreliability. There are moments (like the panel below) when we see Charlie in the dark, and it’s unnerving. He has animalistic qualities. Instincts. He’s dangerous. It’s in his eyes.

And while he speaks up about having sadness, or affection, all we can relate it to is his words and his actions. Now, the actions are pretty straightforward, we see how he reacts, but his words are face value. We have no reason to doubt that he’s feeling sad about something, but his sad and our sad may be entirely different things, and there’s a high probability they are, since he’s a very logic-first kind of thinker.

One of the main things that connects a reader to a character is emotional familiarity. We feel what they feel. We know what they’re going through. There’s still that element in The Darwin Incident, but we have to get it from secondary characters. Charlie doesn’t provide that same attachment, he doesn’t give us familiarity, and that makes him this immensely compelling, emotionally unreliable character that consistently leaves you guessing.

In thinking about unreliable narrators in graphic mediums, I did drum up another example (I’m sure there are others, but let’s stick with one, for brevity’s sake). Jeff Lemire’s run with Moon Knight really brings out the unreliability of Marc Spector. It wonderfully confuses the reader (intentionally) in terms of what’s real, what’s past, and what’s Marc’s detachment from reality. It’s deliberate, and it does a great job keeping the reader off guard.

And so many other mainstream movies and books do the same thing. Fight Club. The Girl on the Train. Lolita. Memento. Literally anything by M. Night Shyamalan. Characters, especially protagonists, deliberately throw you off the scent for a big reveal. Again, it keeps the reader off guard.

Charlie is not that. He is not here to be intentionally confusing or throw the reader off the track of anything. He’s not gimmicky in any way. He’s just naturally unreliable, which adds such an effective layer to a story that already grapples with so much. I mean, I try not to think about theme too much, but The Darwin Incident works in so many relevant, modern themes and makes them feel natural. So of course they can take this emotionally vacant narrator and make him feel natural too.

So how then does Charlie’s emotional unreliability serve the story? Glad you asked. It actually creates something of a unique position with which readers can engage in the story and the themes it presents. Since Charlie is so emotionally removed, we have more to bring to the page as readers. We have to supply our own emotions. I always remember one writing teacher or another saying that sometimes the best thing a writer can do is let the reader do some work of their own.

Charlie lets readers do the work. In his void of emotionality, we bring our own, practically filling it in for him. And that in turn allows us to feel it more deeply. We’re not being told how to feel, we’re in there feeling it. Which is such an interesting turning of the tables because Charlie not showing emotionality essentially pushes us to feel more in his absence. But we also crave knowing just how he does feel. You know that saying that it’s often what you leave unsaid that speaks the loudest? Charlie’s emotional response—or lack thereof, rather—speaks loudly.

It’s a brilliant device that never feels like a device.

As a storytelling element, Charlie’s unreliability actually does keep readers on their toes, even if it’s not like Fight Club. This story could well have taken place with Charlie as a tertiary character, with humans the driving force, so why not opt for that?

Because that’s familiar, and it’s stable. It is, quite simply, unremarkable. Now many stories take an unremarkable set-up and make it pretty great and given the quality of writing in The Darwin Incident, I’m sure that would have been the case. But that’s not the point. The point is, The Darwin Incident sets up remarkably and carries out remarkably.

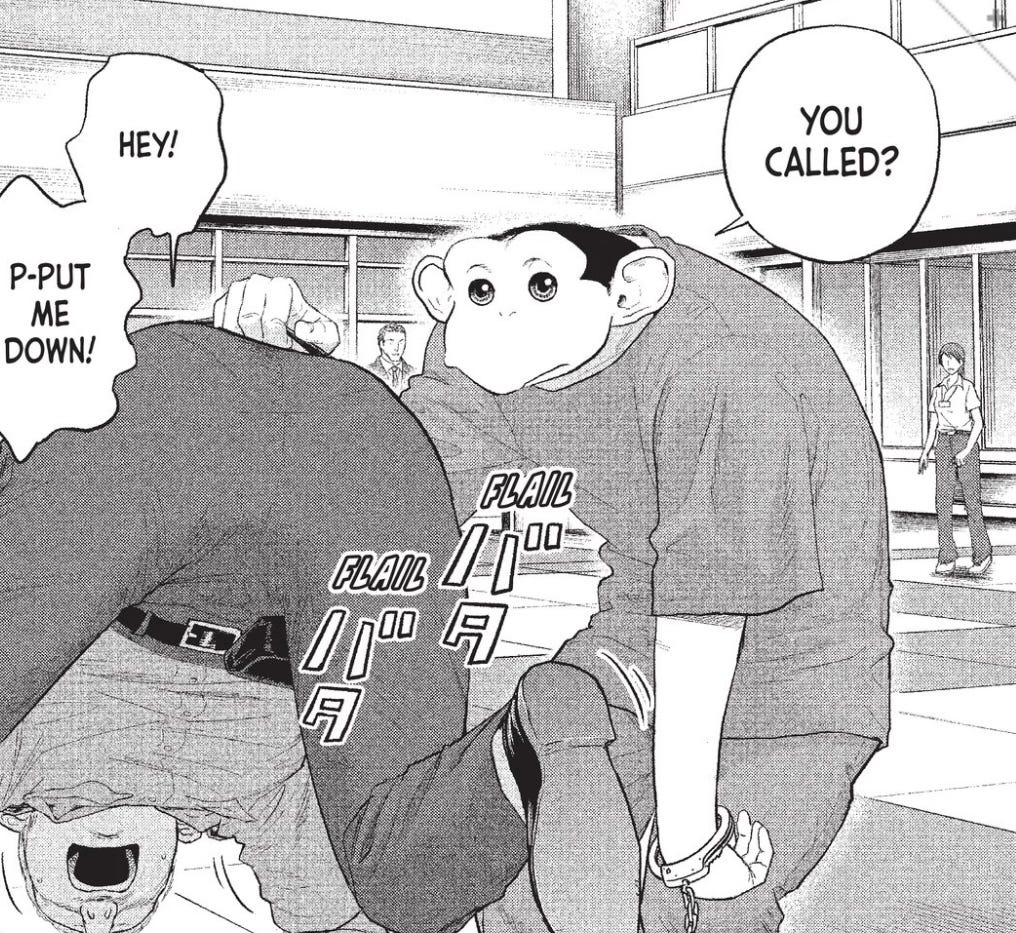

At its simplest, this is the story of a half-human, half-chimp and we just don’t know what he’s capable of or what he’s thinking. His analytical mind is frightening at times, as seen in literally his first school interaction, and that unreliability is like a burning star that keeps deeper themes in orbit.

And, bonus points, because along with this being Charlie’s story, it’s also the best voice with which to face all these themes. Animal rights, veganism, etc. These are themes that are no strangers to the literary limelight, but with a unique narrator, they take on a new perspective.

Okay, a lot of gushing here, but for good cause. What The Darwin Incident presents is a wholly unique story that dips into so many different genres. It almost feels like it’s making its own rules, starting with Charlie.

But before I let you go, here’s a brilliant page showcasing three first-person panels (the kind I said we never see). It also shows just how dangerous (in a good way) Charlie is.

Hey, creatives, how can you muddle your protagonist’s emotionality to create intrigue for readers? Here’s an exercise—give them a concept, dilemma, or emotion they aren’t sure about themselves and portray them grappling with that aspect.

Hey, fans of The Darwin Incident. How do you feel about Charlie, and by that, I mean more than “I like him!” I mean, how do you feel about his morality, his thought process?