The Summer Hikaru Died: Sounds Are Scary

And I'm talking about more than the sounds of silence.

Preface!

This article could not be any more appropriate to my current situation, because I’m writing this from a sketchy cabin in the middle of the Appalachian Trail. A cabin that is full of sounds that are, I don’t know, probably just an old refrigerator or the click of electricity. Probably. Hopefully.

But can I say for sure that it’s not someone trying to break in through the one broken window? Can I say for sure it’s not a wayward cryptic looking for a snack? I can’t. I want to. I’ll keep saying that out loud, but do I know for sure? Nope. I don’t.

That’s the nature of sound. When new sounds introduce themselves, you can convince yourself you know what it is, but without some detective work, how can you know for sure?

Stories—especially horror stories—that use sound well are a cut above. And they’re a big reason why I’m not a fan of this cabin. And also a big reason why I am a big fan of The Summer Hikaru Died.

Preface over.

Think for a second about how fear, or scary moments, approach in a movie or a TV show. In the Babadook, for instance, it’s pretty simple. He approaches by a very gravelly voice saying “Babadook… dook!… DOOK!”

Without that sound, The Babadook would be a much different movie, because it’s not at all about the look of the monster, but rather about the atmosphere that surrounds the monster. It’s why this is my favorite horror movie, and it’s why I referenced it the first time I wrote about The Summer Hikaru Died, in the context of how they both wield subtlety.

The Babadook benefits massively from this sound refrain because it allows them to be subtle. To not rely on the look of a monster which—spoiler—is such a flimsy source of fear. What monster is really that scary looking anymore, in the age of ridiculous CGI? What are you going to do, give them more teeth? More claws? It’s been done.

No monster can exist on looks alone. In any horror movie, sounds—be it music or environmental—swell around approaching scary moments.

Even the old colloquialism—“things that go bump in the night”—is probably one of the most cliched ways to refer to ghosts and other scary things. And it’s all about their sound. Not their look.

That’s all well and good, but how can a book, even a visual one, replicate that ability to harness the power of sound? Maybe you’ve noticed, but books can’t make sounds. At least not in the traditional sense.

That’s where The Summer Hikaru Died excels yet again.

Before we get into The Summer Hikaru Died, here’s what you need to know.

One day, Hikaru comes back from a week missing in the mountains, but it isn’t really Hikaru. His body has been taken by a mysterious entity that doesn’t even understand itself. Hikaru’s best friend, Yoshiki, notices the difference, and gradually, the town begins to descend down a dark path of having to face its own history before it’s consumed by it.

And that’s all you need to know.

The Summer Hikaru Died, much like The Babadook, doesn’t rely on traditional scares. Sure, there are scary things you see, but they’re generally few and far between, which is kind of the point.

That said, for it to be effective horror, sure, you can rely on the few odd visual scares, but there needs to be more there. The Summer Hikaru Died has more everywhere, for the record, but for the point of this article, I just want to talk about the use of sound, because in no other book have I seen sound used as effectively. Not just in making sequences feel more alive, appeal to more senses, and give a more comprehensive experience, but in spreading fear in moments that don’t have dialogue.

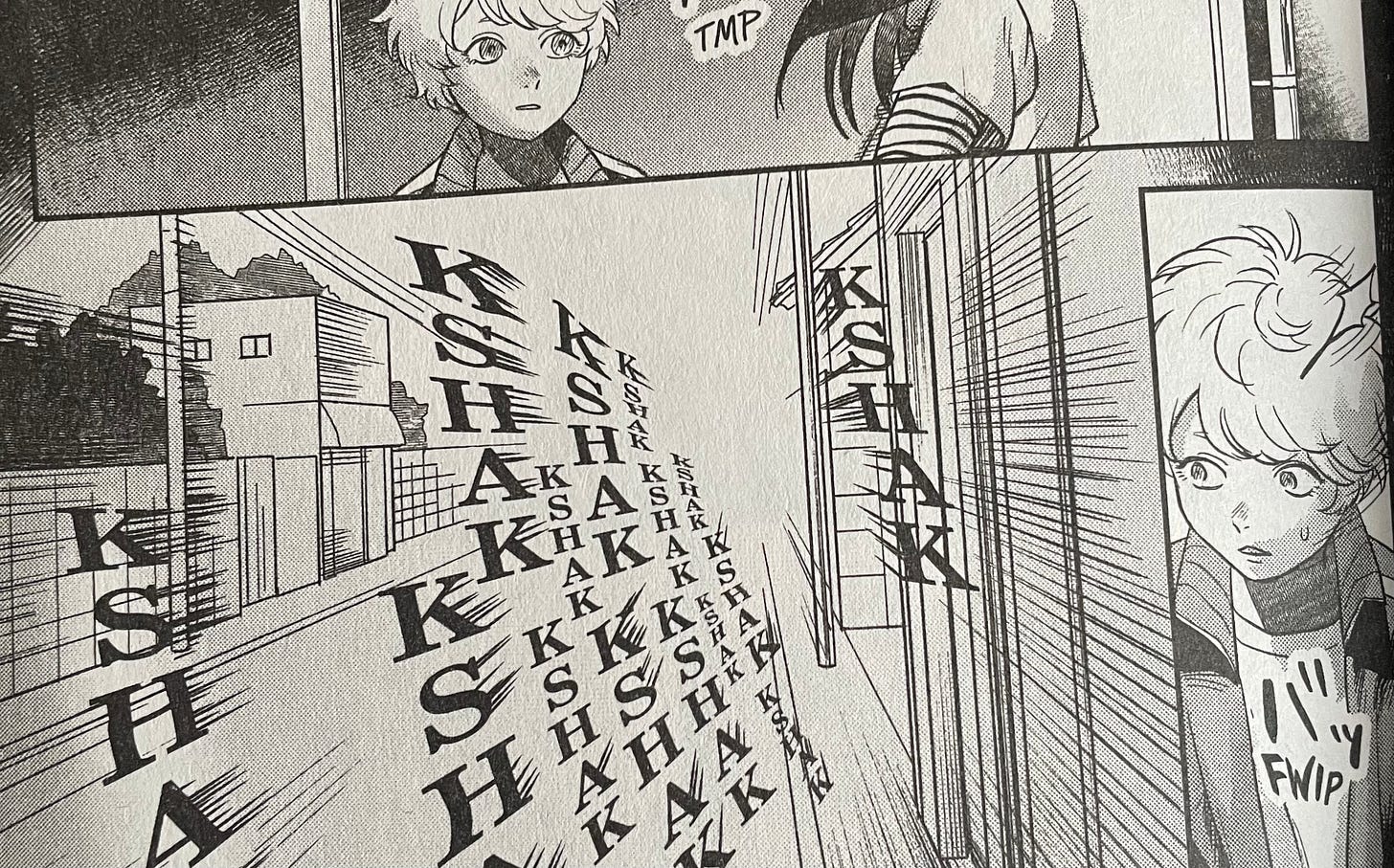

Let’s look at a few examples, so I can stop speaking in generalities. Before we get into the sound device known as Asano, a brilliant character who allows this series to lean even more into sound, let’s look at some straight-up eerie scenes that are only eerie because of the sound.

Why yes, the tick-tock of a clock can be scary, because if you can hear the clock that clearly, then it’s silent all around you. And silence is just as eerie. So this tick-tock becomes a reminder that despite this looming dread over the entire town, Yoshiki is facing an eerie silence. It may just be silence, but… what if it isn’t?

Another example…

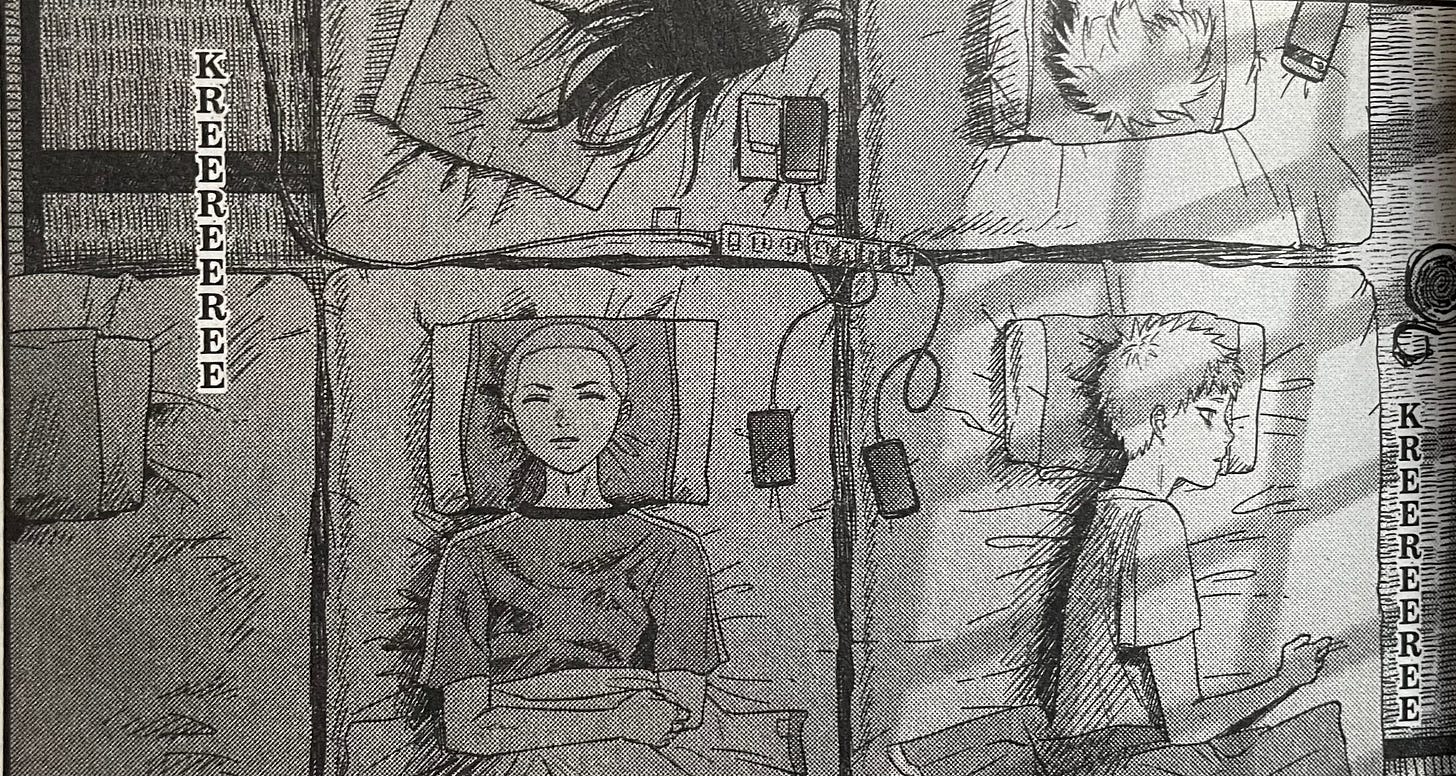

This one is a favorite of mine. They’re having a sleepover, that’s the heads of Yuuki and Asano at the top, Maki looking like he’s asleep and Not Hikaru wide awake. And there, lurking in the edges of our consciousness, some casual kreeeereeeereeeee…

Nothing spooky or eerie about a kreereeereee in the middle of the night, right?

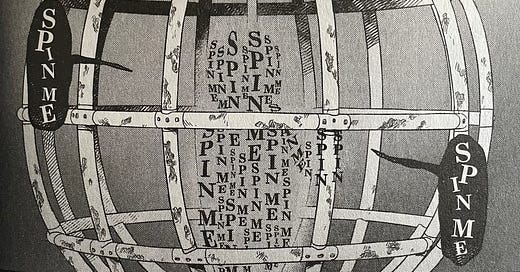

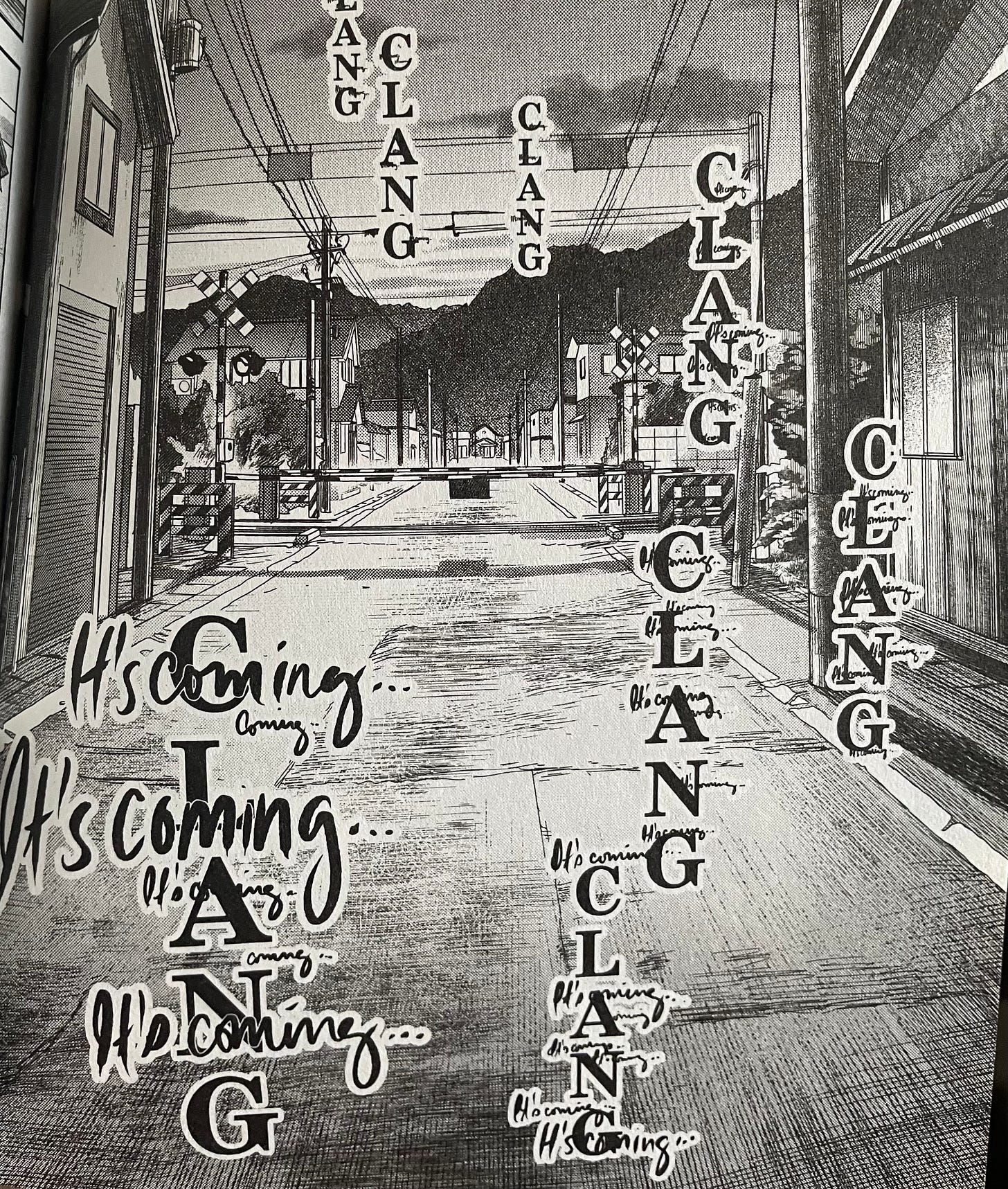

This is a particularly inspired scene. At the train crossing, buried amidst the Clang Clang of the crossing, “It’s coming” is there, almost like a whisper. But the fact that it’s literally hidden inside the Clang’s is what makes it so effective. You can hear this page right? I know I can. I can hear the clanging and the subtle, barely discernible whisper that whatever “it” is, it’s coming.

Okay, now I want to get specifically into Asano, the character who has a physic-like power to hear sounds from the other side. This allows for some really brilliant uses of sound, one of which I’ve already celebrated in previous posts about The Summer Hikaru Died, but I want to touch on it briefly here too.

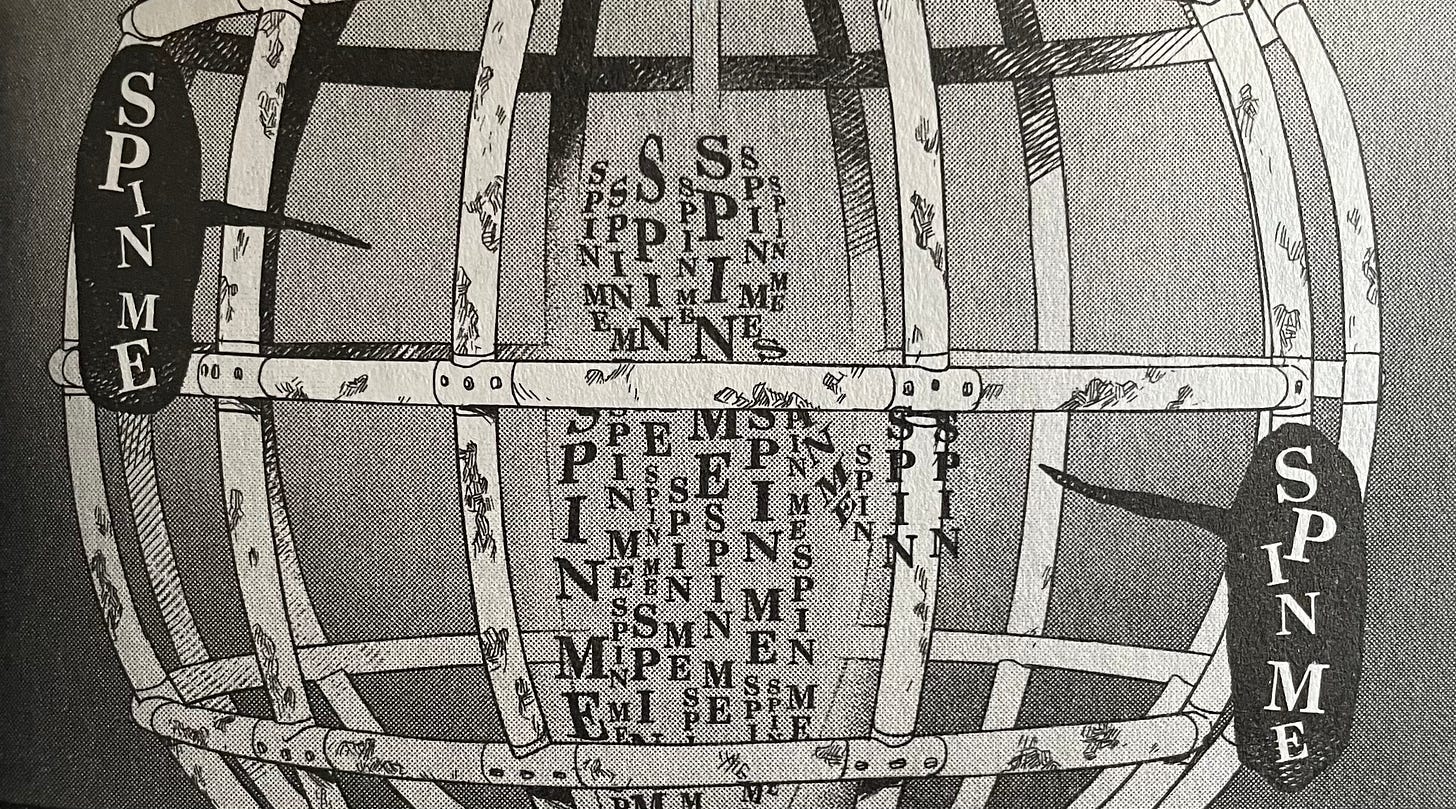

I love this panel so much. Who knew sound could be so scary! Not only is it speaking in darkened speech bubbles and warped text, but the entity itself, vaguely forming the outline of a human, is made up entirely of sounds. Asano cannot see the entity, but she can hear it, and that alone allows her to distinguish where it’s coming from.

A similar example:

What exactly is that? A car? A train? All Asano knows is that it’s a threat and it’s about to hit Yuuki. She runs out to help her friend, but it narrowly misses her.

We never even see what it was. We never know for sure. And that’s part of the brilliance. Since it’s just sound, we can never know for sure what it actually looks like, or what it even is. Even the “Spin Me” entity, sure it looks like a kid, but what does it actually look like. That not knowing is so much scarier than seeing it outright.

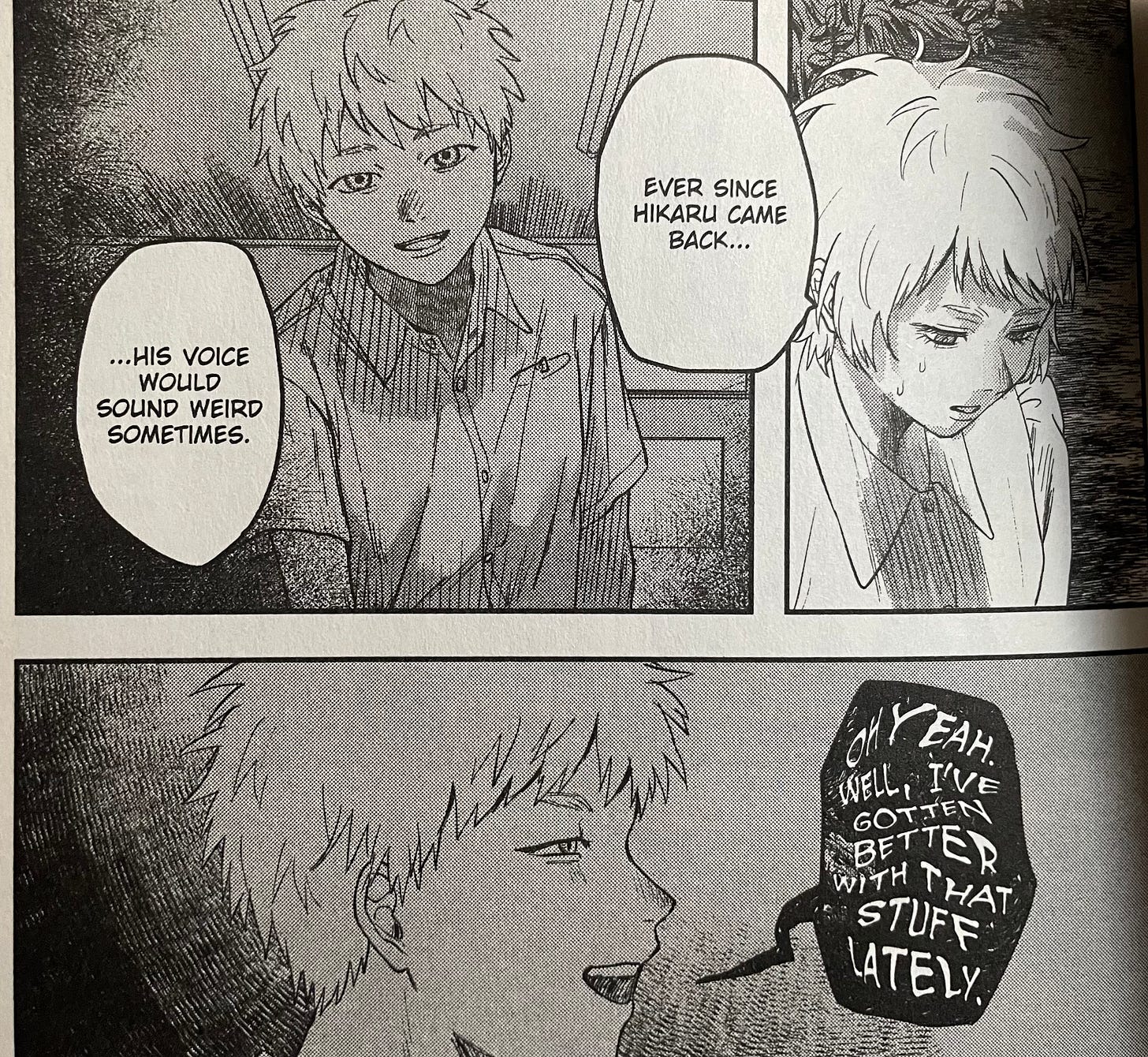

One more example, another favorite.

I love this idea of voices sounding different, and in other manga, there are examples of using different fonts to accentuate vocal changes, but this here is even better, because it’s both a darkened speech bubble, and the words are just distorted enough to make it slightly hard to read.

Which is the only difference Asano can pick out as well.

As I mentioned in the preface, what’s so great about using sound as the font of fear is that it’s difficult to definitively place a new sound. Like the tick-tock in the Yoshiki scene. It could just be a clock, but what if it’s not?

Or, even better, in the sleep over scene. Could just be a tree branch scraping the wall. But can we know for sure? Nope.

That creates a unique horror experience of never being able to really pin down what the source of the horror is, because we can only hear it. That uncertainty, that not knowing, is the same thing that makes me remain just slightly uncomfortable in this cabin full of clicks and creaks.

I’m glad you wrote about this, since I bounced pretty hard off the sound effects in vol 1. After reading this, I’m realizing it wasn’t the sound effects themselves but the graphic treatment of the translation. It’s the font I’m bouncing off of. Makes me wonder what the untranslated version looked like. But given the prevalence of sound in future volumes it makes sense why they translated it. Thanks for the analysis!

It's incredible how a manga can use sound so effectively, I feel like even now that we have the anime to compare it to, the manga is far better at using sounds to create an atmosphere